The historical connection between baseball and the armed forces is substantial and deep-rooted. Players have gone from the ranks into the game dating back to the mid-nineteenth century. Outside of the two world wars, it is not known how many men left the game to join the armed forces.

All eyes of the nation’s baseball fans were affixed on what, as noted by some,[1] was one of the greatest seasons of individual achievement at the plate in 1941. For 63 days between May 15 and July 16, Yankee slugger Joe DiMaggio’s record-setting 56-game hitting streak captivated not only Yankee fans but even the most casual observers of the sport.

Following his May 2, 1941, zero-for-three showing in Cleveland against Indians pitchers Mel Harder and Joe Heving, Red Sox slugger Ted Williams was at the low point of his season batting average at .308. After a four-for-five and a two-for-three showing in a September 28 season-ending double header in Philadelphia, Williams finished with a .406 average and remains the last batter to hit .400 in a season.

In addition to DiMaggio’s and Williams’ individual accomplishments in 1941, the historically hapless Brooklyn Dodgers captured their first National League pennant since 1920, becoming a bit of a Cinderella story.

The 1941 season was certainly cause for celebration in the United States and served as a healthy distraction to the horrors that were taking place in far-off lands. As the Imperial Japanese were swallowing up territory in the Far East and the South Pacific and wreaking destruction upon millions of conquered people, the Third Reich was expanding its reach, capturing most of western Europe. From March, 1938 through December, 1941, Germany brutally invaded Czechoslovakia, Poland, Denmark, Belgium, France, and Russia. It launched incessant bombing missions upon England from July through October, 1940. Hundreds of thousands of people were being killed by the Axis powers. Germany put Hitler’s plan, “the final solution to the Jewish problem,” into action. A shroud of darkness was swallowing the globe. The 1941 baseball season certainly shielded the American population from what was happening away from the shores of the United States.

As war was raging across the Atlantic and Pacific, the United States was slowly building up its military from dramatically reduced peacetime strength. President Roosevelt signed an executive order instituting a peacetime draft with the Selective Service act of 1940.[2] The bulk of the Navy’s battleships were built before, during and immediately following the Great War and were badly outdated despite modernizing efforts. To better position the defense of the United States against the growing Japanese threat, the Pacific Fleet was shifted from the West Coast to Hawaii while shipyard facilities were ramping up with new construction and modernization activities.

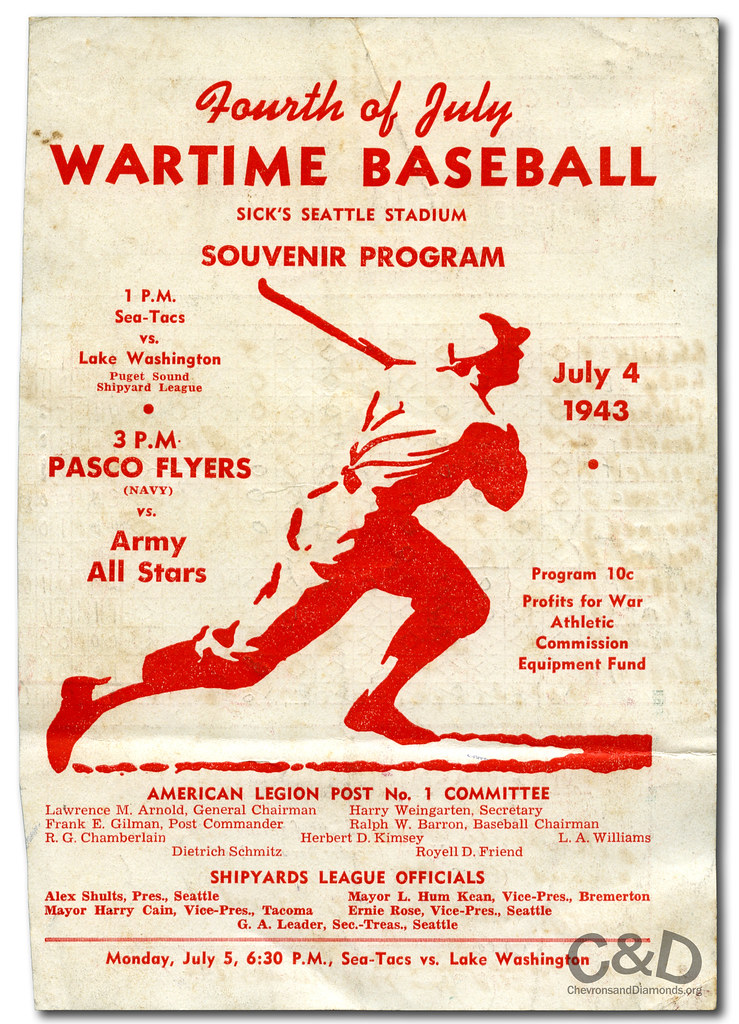

During the interwar period Navy athletic competition was highly popular. Ships of all sizes fielded teams to compete in sports including football, basketball, swimming, rowing, tennis, golf and others. America’s pastime held true for Navy athletics with teams vying for squadron, division, fleet and Navy-wide championships each year. In some instances, the Navy’s best ballplayers were heavily pursued by ship commanding officers to gain advantage and would apply leverage to get those men assigned to serve aboard with the hope of securing the coveted championships.[3] Due to the game’s popularity, it would have been more of a challenge to find an American young man lacking baseball experience than to find one with well-developed skills. Many players entered the service with high school, college, sandlot, semi-professional, or even minor league experience.

The 1941 baseball season in the Pacific Fleet faced challenges due to naval exercises, maintenance and refit schedules and other ship-movement activities. Games between shipboard teams had to be scheduled and re-scheduled according to the needs of the Navy, which took priority over the desire for baseball championships on the part of the commanding officers and ball teams.

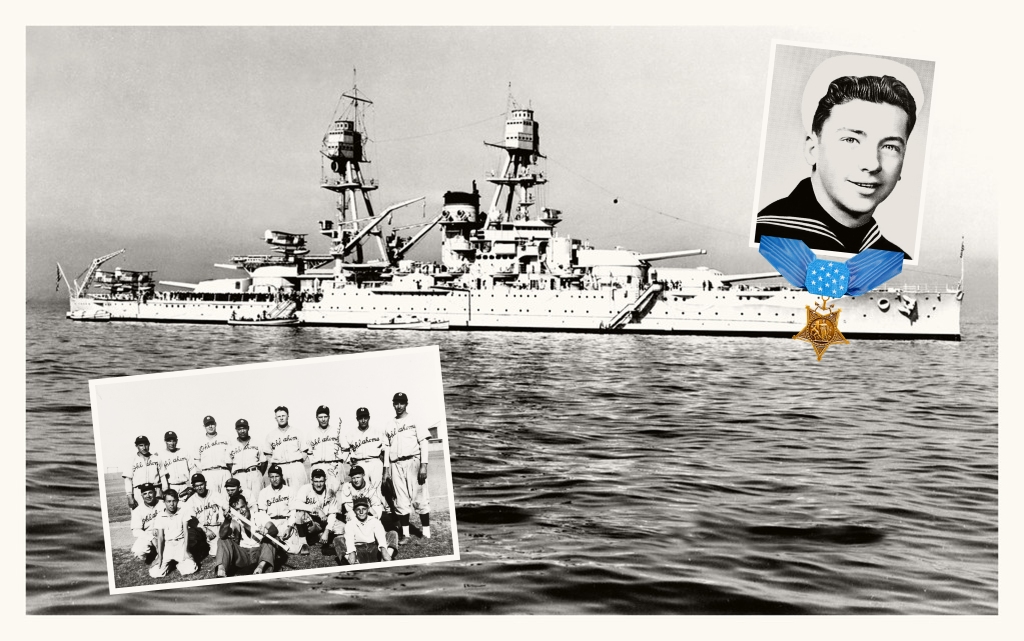

Among the Pacific Fleet battleships, the USS Mississippi (BB-41), USS Colorado (BB-45), USS California (BB-44), USS Arizona (BB-39) and USS Oklahoma (BB-37) fielded the frontrunners in their respective battleship divisions. By mid-May, the Indians of the USS Oklahoma, Battleship Division Two champions, were squaring off against the “Wildcats” of the USS Arizona, winners of the Battleship Division One crown in a three-game elimination series for the championship of their group.[4] Meanwhile, the “Bronchos” of Battleship Division Three champion USS Colorado took on the mighty Mississippi men, reigning Pacific Fleet Champs and current Battleship Division Four kings for the Group 2 title.[5]

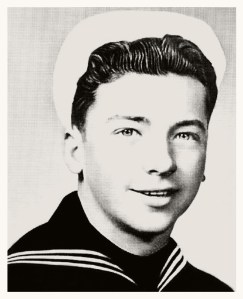

The USS Oklahoma Indians were fast becoming the top contenders for the Pacific Fleet baseball crown. Indians shortstop Seaman First Class James R. Ward wrote home about his experiences on the team during his first season, “Not to brag, but they think I’m pretty good,” he stated. “That helps when you want to get an apple or something between meals. If I want a haircut I don’t have to stand in line,” Ward wrote about the celebrity-like benefits to the team’s and his success, “I just go right up on to the front.”[6]

Ward also wrote home that he was playing third base for the ship and was batting .583.[7]

“Not to brag, but they think I’m pretty good”

– Seaman 1/c Dick Ward, 1941 letter to his parents

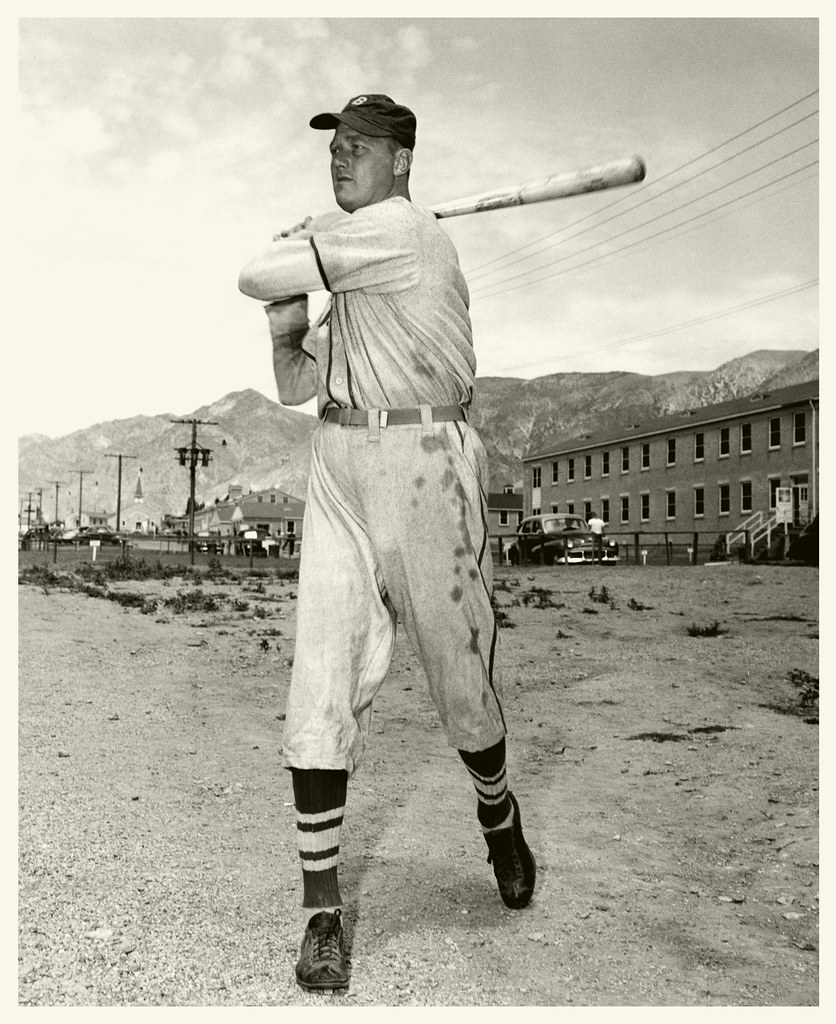

James Richard Ward was born on September 10, 1921, in Springfield, Ohio to Howard J. and Nancy M. (nee Redmond) Ward. The elder Ward worked as a painter for the Chaney Manufacturing Company., a thermometer manufacturer. When he was seven years old, his sister Marjorie arrived into the Ward family. Known as Dick to his family, Ward enjoyed participating in sports year-round. When he was twelve Dick’s approach to baseball became more serious and would remain so for the rest of his life.[8]

Not only did he excel in the game at both the junior and senior high school levels, but he joined Springfield’s Pumphouse All-Stars in the Junior Sandlot Division before moving up to the leagues Senior circuit. In addition to playing in both divisions, he coached the Pumphouse Cub Division youth team. In his senior year of high school, Dick Ward also played for the local American Legion team, seldom striking out at the plate.[9]

A town situated 25 miles northeast of Dayton, the population of Springfield, Ohio was more than 70,000. While baseball was the most popular sport in America at the time, the nearest municipality with a professional ballclub, the St. Louis Cardinals’ class “AA” Redbirds, was Columbus, 50 miles due east. Despite the size its population for the last 80 years Springfield has produced more than its fair share of major and minor leaguers including Harvey Haddix, Adam Eaton, Dustin Hermanson, and Jimmy Journell. Three of Springfield’s ballplayers spent parts of their careers with Ohio’s major league clubs: Brooks Lawrence and Will McEnaney who both played for the Cincinnati Reds; and Dave Burba with Cleveland. Rick White, J. T. Brubaker, Derek Toadvine, Nicholas Wagner and James Murphy, had minor league careers.

From Ward’s alma mater, Springfield High School, four men spent time in the minor leagues: Dick Stoll, Ralph Lucas, Stephen Christopher, and Luther Burns. Pitcher Sam Woods, class of 1938, began his professional career with the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League after serving in the Army during the war.

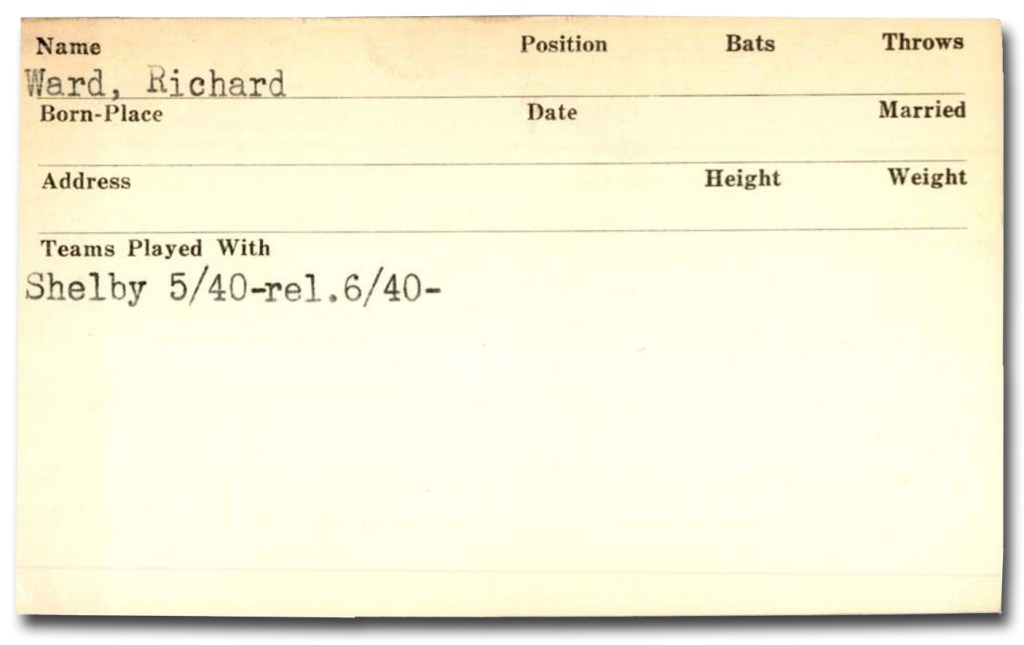

Ward graduated from Springfield High School in June 1939 when he was 17 years old. He went to work straight away in the glass shop of Chaney Manufacturing where his father was employed. Dick continued playing sandlot baseball until he was signed to a minor league contract with the Shelby Colonels of the class “D” Tar Heel League in Shelby, North Carolina, in May 1939. The Colonels, managed by Lou Haneles, were off to a terrible start, losing considerably more games than they won. Seeking to right the ship before the season got too far out of hand, the club signed “prospective big league farm men,”[10] supplanting Ward before he had a chance to appear in a game. Ward was released the following month.[11]

Out of organized ball, Ward hired as stoker at Steel Products Engineering Company,[12] which produced automatic coal burners and stokers which were integral in residential coal and oil furnaces for home heating.

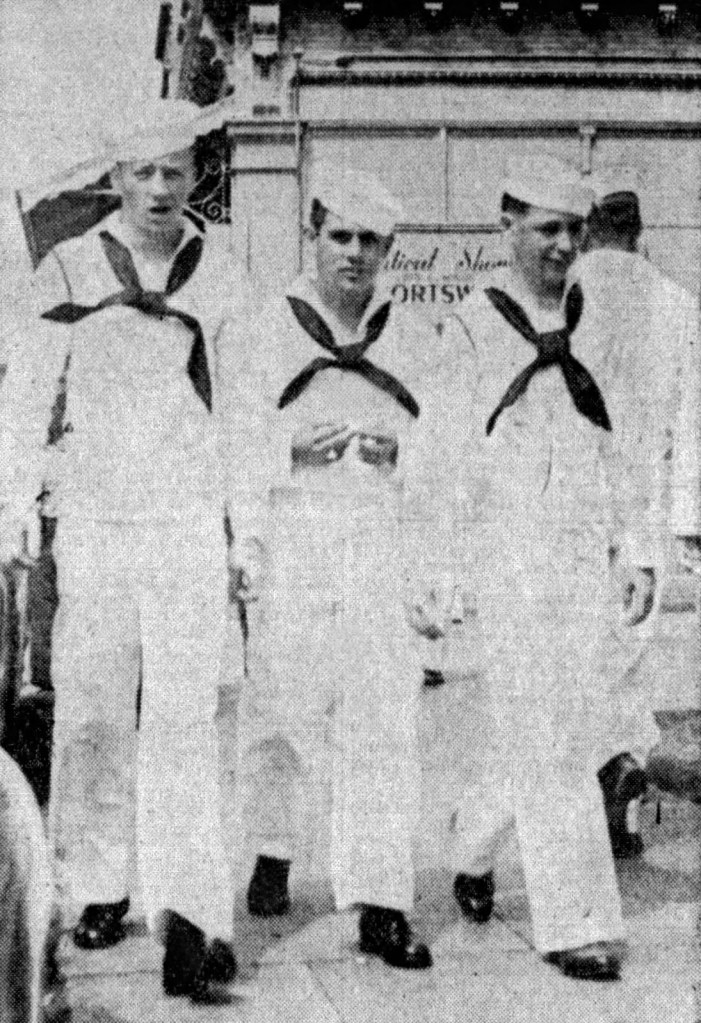

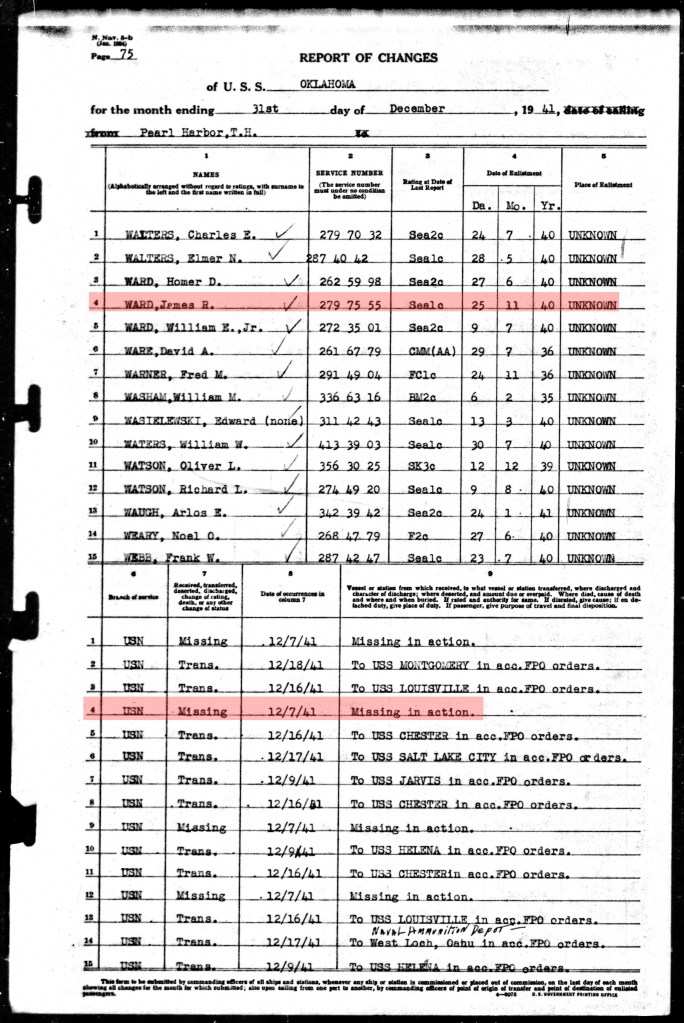

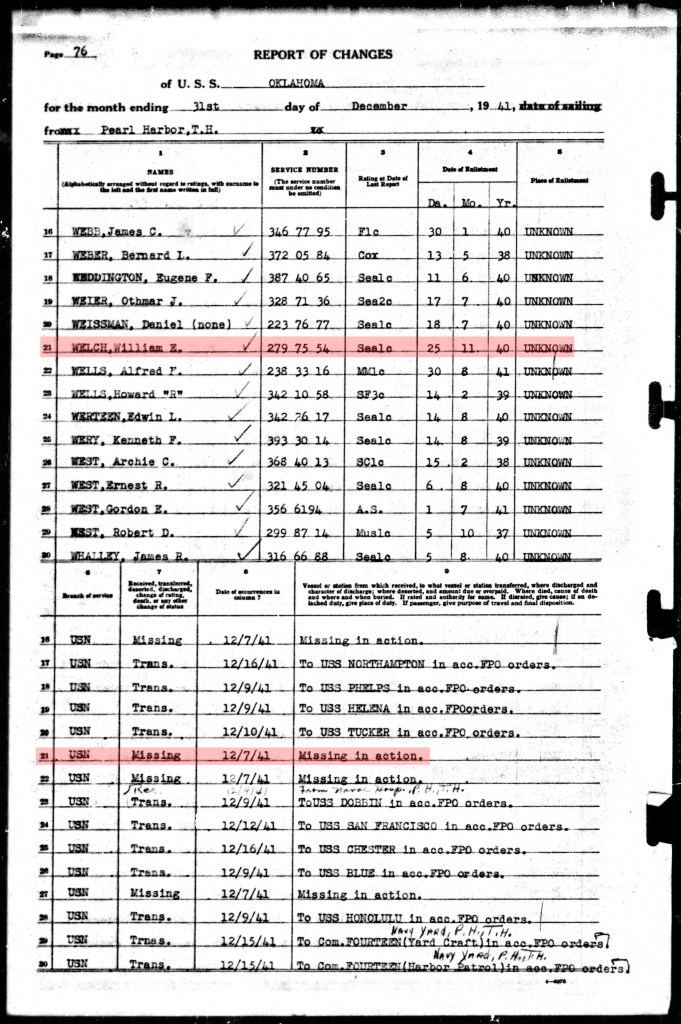

On November 25, 1940,[13] Dick Ward and his longtime childhood friend Eddie Greaves were joined by another friend, William Welch as they enlisted in the U.S. Navy.[14] The three young Ohio men reported to Great Lakes Naval Training Station for bootcamp. Two months later, two of the three young sailors, Ward and Welch reported aboard USS Oklahoma on January 27, 1941.[15]

Life aboard the battleship was not easy for a junior seaman with the daily routine of cleaning, chipping, and painting and other maintenance along with watch standing duties, regardless of whether the ship was at sea or in port. Months before Ward arrived, the ship shifted homeports from California to Pearl Harbor in accordance with President Roosevelt’s decision to demonstrate the Navy’s far-reaching presence in the Pacific. As tensions continued to rise while the Empire of Japan aggressively expanded its territory, the fleet, already in port at conclusion of Fleet Problem XXI[16] in May 1940. For the sailors on the ships at Pearl Harbor, liberty call meant easy access to the beaches and shopping for goods not seen in middle America. Nancy Ward received a gift of a “real Hawaiian kimono” from her son, despite the size 52 garment being considerably large for her size 14 frame. Dick’s sister Marge received a grass hula skirt while his father enjoyed the wooden smoking kit he also sent.[17]

Once aboard the ship, Ward found his way onto the Oklahoma’s baseball team and enjoyed the benefits of being on a winning team. “I don’t know if I told you, or not,” Seaman Ward wrote to his parents, “but our team won the championship of the fleet.”[18] Pacific Fleet champions in 1939, the Indians retained several of their key players including backstop Gunner’s Mate Third Class Lanie C. Quattlebaum, pitching ace “Matty” Matthews, left fielder Mess Attendant First Class Otis Johnson, infielder Seaman First Class “Art” Cavalluzza, and first baseman Lieutenant William T. Ingram,[19] who managed the club. Ward’s prowess on the left side of the infield and his sure batting bolstered the team.

“No, sailors don’t play baseball on the landing decks of airplane carriers,” Ward wrote home. “They play on dry land when ‘the fleet is in.” It is unclear which championship Dick Ward was referring to in his letter, but he was likely referencing the Battle Fleet title. “And I was the batting champion,” Ward remarked.[20] When the ship was in port that year, Oklahoma’s crew participated in athletics including basketball, golf and boxing, in addition to baseball.

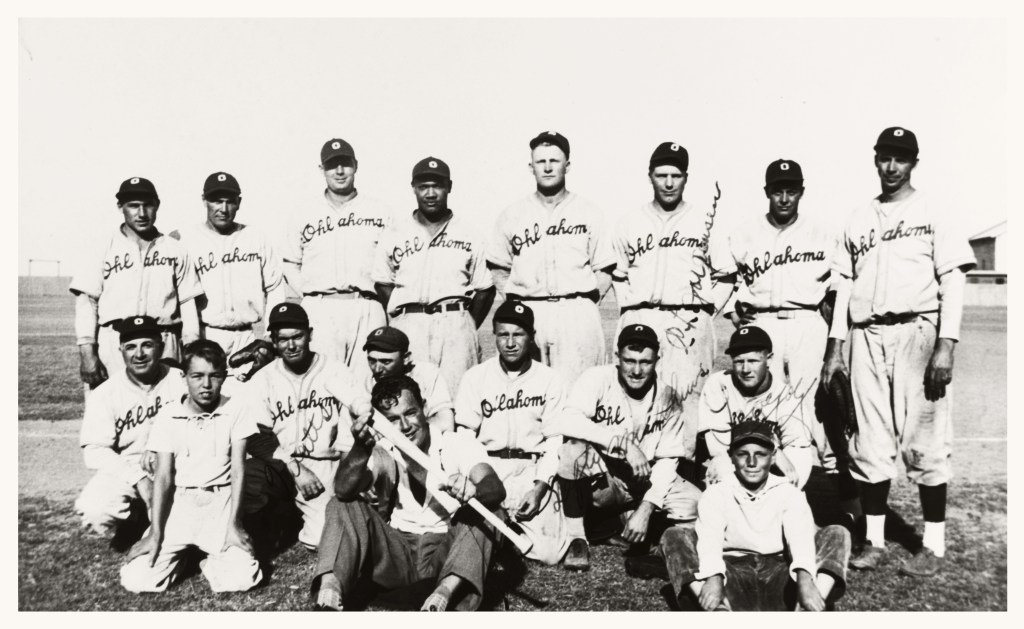

1941 USS Oklahoma Indians:

| Rank | Player | Position |

|---|---|---|

| MM1/c | Paul P. “Busty” Bestudik | CF |

| “Swede” Carlson | P | |

| Sea1/c | Richard J. “Cavvy” Cavalluzza | IF |

| CSK | Harry Compton | Mgr. |

| Sea1/c | Kenneth Griffith | 3B |

| LT | William T. “Bill” Ingram[21] | 1B |

| MATT1c | Otis Johnson | LF |

| Knight | LF | |

| F1/c | George W. “Matty” Matthews | RF/P |

| WT1/c | Bernard E. “Pick” Pickett | RF/P |

| GM1/c | Lanie Clenton Quattlebaum | C |

| Rainier | C | |

| “Rosy” Riskosky | C | |

| Sea1/c | Glen J. Timmons | 2B |

| Sea1/c | James Richard Ward | SS |

While the Indians had the likes of pitcher Matty Matthews and catcher Lanie Quattlebaum, the USS Oklahoma’s main battery consisted of ten 14-inch guns mounted on four turrets: a pair of triples and a pair of twin mounts. Seaman Ward was a member of one of the ship’s turret crews, participating in gunnery competition that concluded in June. The pointers of turret number 3, the after twin 14” mount, were awarded medals by the Admiral Trenchard Section Navy League for the highest merit of short-range gunnery during fleetwide competition.[22]

Much of the baseball season’s playoffs for the Pacific Fleet were decided through May as the Navy’s operational, training, and planned overhaul schedules ran up against normal baseball season schedules. On October 22 during a naval patrol in Hawaiian waters, USS Oklahoma was operating with USS Nevada (BB-36) and USS Arizona. Sailing under blackout conditions to conceal the ships from potential enemy threats, the three battleships were steaming in formation as Oklahoma began to unknowingly slip out of position. Sensing the dangerous potential for collision, the lights were ordered to be illuminated showing the Arizona nearly alongside. Both ships ordered evasive maneuvers, however Oklahoma contacted Arizona’s port. Both ships were harmed in the collision though the damage to Arizona was much more substantial with a 14-foot gash into the port side of her hull.[23]

USS Arizona had been slated to begin an extended overhaul at the Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton in the following weeks but was delayed until mid-December, necessitated by repairs from the collision. During the following weeks as repairs were made to Arizona, the Pacific Fleet baseball championships[24] were shaping up.

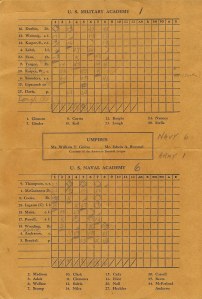

Playing their way into the title game against the USS Oklahoma Indians, the Pearl Harbor Submarine Base’s Subron Four club featured some of the Navy’s best ballplayers. With a pitching staff led by longtime veteran Chief Boatswain’s Mate George “Nig” Henry who won fleet championships dating back to the 1920s when he hurled for the USS New Mexico (BB-40) team, the Sub Base team was historically one of the strongest teams in the islands, season after season.[25] Having defeated the tough USS Northampton (CA-26) club in the Pacific Fleet Championship semi-finals in an earlier day game on November 27,[26] the Subs demonstrated that they were a formidable opponent.[27]

Two years after winning their last fleet title, Indians manager Lieutenant Bill Ingram put his best up against Subron Four. The dominant battery of Matty Matthews and Lanie Quattlebaum could hold their own against any opposing offense and Ingram stayed with the consistent pitching and catching combination that was responsible for a substantial number of the Oklahoma’s victories dating back to 1939. Batting in the ever-important leadoff spot, Dick Ward was stationed at shortstop. Rounding out the batting order were Quattlebaum, “Busty” Bestudik in center, Bill Ingram at first base, “Pick” Picket in rightfield, Glen Timmons at second, Knight in left, Ken Griffith at third and Matthews.[28]

For five straight innings, Subron Four’s Stevenson held the Indians scoreless with masterful pitching while Sub batters plated runs on Matty Matthews in the bottom of the first, second and fifth innings. In the Indians half of the sixth, Ingram smacked a solo shot beyond the right field fence to put the Oklahomans on the board.[29]

Trailing 3-1 in the seventh, the battleship guns sprang into action. The bottom of the Indians’ order rocked Subron Four’s Stevenson for successive blows. Timmons, Knight, Griffith, and Matthews fired back-to-back-to-back-to-back solo homeruns to force Subron Four’s manager, Dutch Raffeis to pull his pitcher. To quiet the battleship’s bats, George Henry took over to force the Indians into a cease-fire. The damage was done and Subron Four was trailing by two runs heading into the bottom of the frame.[30]

The submariners fired a spread of their own in the bottom half of the seventh, capitalizing on an Indians miscue by Ward that resulted in a pair of runs to knot the score at 5-5. Manager Ingram relieved Matthews in a position swap with “Pick” Picket to keep Matty’s big bat in play. The Oklahoma men were unable to break the tie in the top half of the eighth however in the bottom half an error by Matthews in right field led to a Subron Four tally to put the Indians into arrears by a run heading into the top of the ninth. “Nig” Henry handcuffed Indians batters to preserve the 6-5 victory, wresting the Pacific Fleet crown away from the USS Oklahoma.[31]

After their Indians fell a run short in the championship game, the USS Oklahoma put to sea with the USS Arizona and USS Nevada undertaking various tactical maneuvers in Hawaiian waters. “We had been conducting exercises and were proud to have done well in gunnery with our main, broadside, and antiaircraft batteries. We were battlewagon sailors,” Chief Warrant Officer Henry A. Long, Jr. recalled years later.[32] On December 5, the Oklahoma returned to Pearl Harbor, mooring with her starboard side to, outboard and abreast of USS Maryland’s port side. The Maryland (BB-46) was moored against the concrete quays (berth F-5), ahead of the Tennessee which had the USS West Virginia (BB-48) breasted on her outboard side (berth F-6). Astern of Tennessee and West Virginia were (in berth F-7) the USS Arizona and USS Vestal (AR-4) with the Nevada last in the line of eight Ford Island quays directly across the South Channel from the Pearl Harbor Supply Base.

On Sunday morning, as sailors stood at the ready at each ship’s flag and jack staff, just moments before the first notes of the Star-Spangled Banner were set to play, the skies were suddenly abuzz with aircraft. Small geysers erupted across from battleship row and seconds later the first Japanese aerial torpedo struck the ship. Realizing the ship was under attack, men began to run to their battle stations. As a relaxed Sunday morning routine was the norm of the day, many men were still asleep in their berthing compartments. As they leaped to their feet in response to the emergency, some of the crew did not have time to dress or put shoes on. Within ten minutes, the ship was hit by seven more as she began to roll.

“I was in the lower handling room of Turret IV. After the first hit, I went to the shell deck. The lights went out and the ship started to turn over,” Seaman First Class D. Weissman recalled years later. “I went to the lower handling room and followed a man with a flash light. I entered the trunk just outside of handling room on the starboard side,” Weissman continued. With the ship still rolling as water poured through the massive damage in the hull, escape from below decks became almost impossible. “The lower handling room flooded completely. Water entered the trunk. I dove and swam to the bottom of the trunk and left the ship through the hatch at the main deck and swam to the surface,” Seaman Weissman described his escape.[33]

After the attack was over and the Japanese aircraft returned to their carriers, battle in the harbor was far from over. All the battleships that were moored along Ford Island were heavily damaged or resting on the bottom as fire raged. The overturned Oklahoma still had men trapped inside and the Arizona was a complete loss. Hundreds of sailors, Marines, airmen, and soldiers were dead or missing and many more were wounded and severely burned. When all personnel were finally accounted for, the final death toll reached 2,403 with men entombed in the wrecks of Arizona, Oklahoma, and USS Utah (AG-16).

After the news of the attack spread across the United States, families of those serving aboard ships and military bases around Oahu awaited word from their loved ones. Three days after the attack, families were being notified of those who were safe, wounded, killed or missing. On the sixth page of the Springfield Daily News were six photos of local area men who had yet to get word home of their status. The second photo at the top of the page showed James R. Ward as one of the men.[34]

Two days before Christmas, the Navy dispatched telegrams to two Springfield families, notifying them that their sons were officially classified as missing. Both men were USS Oklahoma sailors who had enlisted together: Seaman William E. Welch and Seaman James R. “Dick” Ward.

Stories of individual bravery and heroism began to surface in the days and weeks after the attack. Of the 62 medals for heroism, courage, gallantry and valiant conduct, 51 were Navy Cross medals bestowed upon sailors and marines. Another 272 letters of commendation were presented to both Pearl Harbor and Wake Island service personnel following the attacks.[35] Of the 14 Medals of Honor (MOH)[36] bestowed upon men who exhibited valor during the Pearl Harbor attack, two of them went to USS Oklahoma sailors. Coincidentally, the circumstances prompting each of the sailors’ actions are the same and their MOH citations are nearly identical.

“The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pride in presenting the Medal of Honor (Posthumously) to Ensign Francis Charles Flaherty (NSN: 0-95690), United States Naval Reserve, for conspicuous devotion to duty and extraordinary courage and complete disregard of his own life, above and beyond the call of duty, during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, by Japanese forces on 7 December 1941. When it was seen that the U.S.S. OKLAHOMA (BB-37) was going to capsize and the order was given to abandon ship, Ensign Flaherty remained in a turret, holding a flashlight so the remainder of the turret crew could see to escape, thereby sacrificing his own life.”[37]

Recalling Seaman Weissman’s description of his escape from turret number four, one could easily draw a conclusion that Ensign Flaherty’s actions helped to save the lives of the men in that turret, however, Ensign Flaherty served as the Assistant First Division and Turret Number 1 Officer. Upon hearing the order to abandon ship, Flaherty recognized that his men in the turret were in great danger with the ship flooding, dark, and beginning to roll over, leading him to take action to illuminate a way for his men to escape. Seaman First Class Ward “knew his shipmates would be trapped in the turret [number 2] as the ship rolled over so he too shined a light down through the turret so the men could come up from below and go out the hatch in the overhang,” author Stephen Bower Young wrote in his book, Trapped at Pearl Harbor: Escape from Battleship Oklahoma. Flaherty and Ward, “officer and seaman, hung on desperately, remaining behind as the turret crews abandoned, assisting and urging on the sailors remaining so they would not die, trapped in a sinking ship.” [38]

After his family was notified by President Roosevelt and Navy Secretary Frank Knox, the local newspaper carried word that Dick Ward was to be presented the nation’s highest military decoration. “I deem it an honor to transmit to you the Congressional Medal of Honor and citation awarded your late son, James Richard Ward, seaman first class, United States Navy,” the letter from Secretary Knox stated in a letter, “by the President of the United States in the name of Congress for his conspicuous conduct in the line of his profession.”[39] Dick Ward, the star ballplayer from Springfield, Ohio was a hero.

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pride in presenting the Medal of Honor (Posthumously) to Seaman First Class James Richard Ward (NSN: 2797555), United States Navy, for conspicuous devotion to duty, extraordinary courage and complete disregard of his life, above and beyond the call of duty, during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, by Japanese forces on 7 December 1941. When it was seen that the U.S.S. OKLAHOMA (BB-37) was going to capsize and the order was given to abandon ship, Seaman First Class Ward remained in a turret holding a flashlight so the remainder of the turret crew could see to escape, thereby sacrificing his own life.[40]

In 1943, in a feat of naval engineering, the hulk of the USS Oklahoma was raised from the Pearl Harbor mud, patched, refloated and uprighted to be salvaged for scrap metal. During that process, the badly decomposed remains of the 429 entombed sailors were removed from the stricken vessel and buried in mass graves at the National Memorial of the Pacific, located in the Punchbowl volcanic crater overlooking Honolulu. Each grave marker states the number of unknowns from the ship that are interred in the specific plot. Due to the state of decomposition of the recovered bodies, some graves hold the remains of as many as ten Oklahoma sailors. Among the unknowns buried at the Punchbowl Cemetery were Springfield, Ohio’s Bill Welch and Dick Ward.

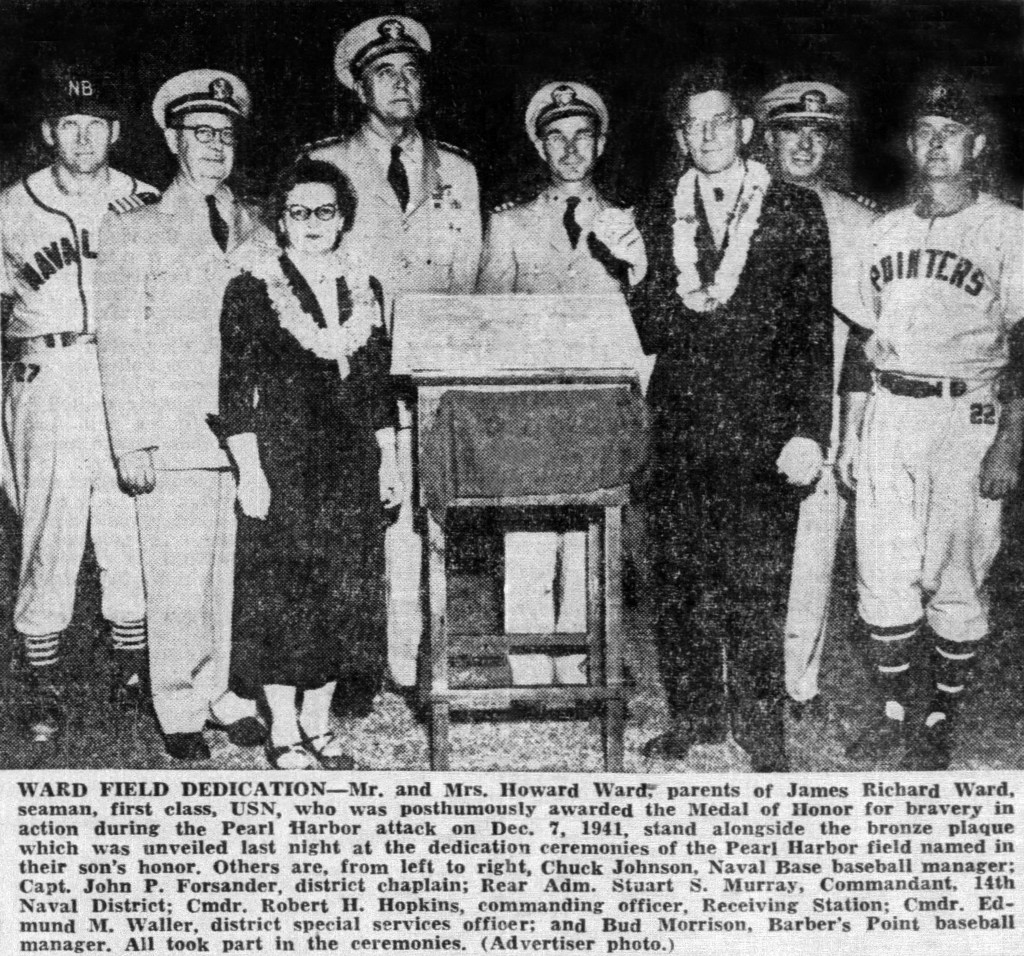

On April 8, 1953, more than 11 years after starting shortstop Seaman First Class James R. “Dick” Ward, the only member of the 1941 USS Oklahoma Indians ball team to perish in the Pearl Harbor attack, his parents, Mr., and Mrs. Howard Ward were guests of Rear Admiral Stuart S. Murray, Commandant of the 14th Naval District for a special pregame ceremony as the Pearl Harbor Naval Base played host to the Barber’s Point “Pointers.” Bounded in a triangle area between Center Drive, “N” Road and Battleship Drive at the foot of Pearl Harbor’s Southeast Loch by Merry Point Landing, a new ballpark was constructed on the Pearl Harbor Naval Base. Recognizing Seaman Ward’s sacrifice on December 7, 1941, and his outstanding baseball play that season, the Navy honored him by naming the new ballpark Ward Field. The athletic field would host many types of sports including baseball. Rear Admiral Murray unveiled a bronze plaque that was placed near the entrance of the field.[41]

For decades, the Department of Defense has been working tirelessly to narrow the list of service members listed as missing in action to provide closure for surviving family members. With the advancement of DNA extraction and testing technologies, many breakthroughs in identifying the remains or previously unknown deceased armed forces personnel. With the January 30, 2015 establishment of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), multiple agencies were joined together to create a single organization to accomplish the mission to restore the unaccounted-for service personnel.[42]

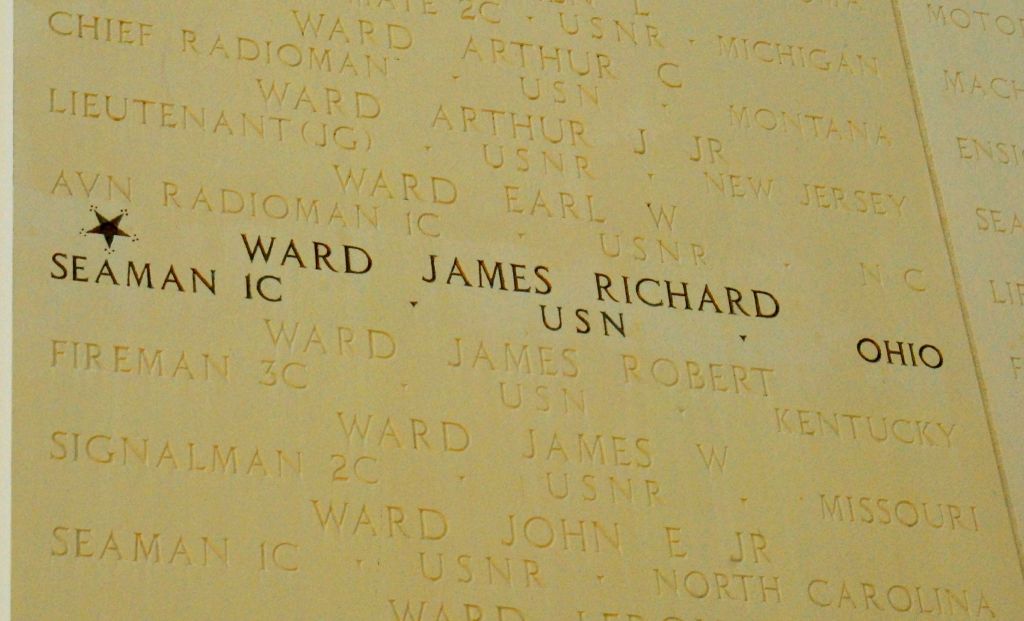

One of the first actions taken by the DPAA was to request and receive authorization in 2015 to exhume unknown remains associated with the Oklahoma from the Punchbowl Cemetery graves and reexamine them using advances in forensic techniques. Since that year, 322 USS Oklahoma sailors’ remains have been positively identified.[43] On August 19, 2021, Seaman First Class James Richard Ward’s remains were identified by the DPAA and his family was subsequently notified weeks later, September 3.[44]

During the summer of 2023, the DPAA published an announcement regarding the final resting place of Seaman Ward. After 72 years of being interred as an unknown at Punchbowl Cemetery, Ward would be laid to rest among the nation’s heroes at Arlington National Cemetery at a future date to be announced. At present, Ward is recognized in his hometown with a monument at Ferncliff Cemetery in Springfield, Ohio, and on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

Two former minor leaguers, Marine Corps First Lieutenant Andrew J. “Jack” Lummus,[45] who played one season of minor league baseball with the class “D” Wichita Falls “Spudders” of the West Texas-New Mexico League, and T/5 John J. “Joe” Pinder, Jr., U.S. Army,[46][47] who pitched for four clubs from 1935-1941, also in class “D,” were the only known former professional baseball players to receive the Medal of Honor.[48] While Seaman First Class James R. “Dick” Ward’s service, sacrifice and decoration were well-known, his brief time in 1940 in organized baseball was not present-day common knowledge.

On December 7, 2023, the announcement was made regarding the interment ceremony for Seaman 1/c James R. Ward to be held on December 21, 2023 at Arlington National Cemetery. “Certainly with his actions, he deserved to be in hallowed ground,” said Richard Hanna, 67, Ward’s nephew in a Dayton Daily News article.[49]

[1] Creamer Robert W. 1991. “Baseball in ’41: A Celebration of the Best Baseball Season Ever– in the Year America Went to War,”. New York N.Y. U.S.A: Viking.

[2] David Vergun, “First Peacetime Draft Enacted Just Before World War II, (https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/story/Article/2140942/first-peacetime-draft-enacted-just-before-world-war-ii/)” U.S. Department of Defense, April 7, 2020 (accessed November 8, 2023).

[3] M. Shawn Hennessy, “’Dutch’ Raffeis: The Navy’s Own Flying Dutchman (https://studiogaryc.com/2023/03/10/dutch-raffeis/),” The Infinite Baseball Card Set: March 10, 2023 (accessed November 8, 2023).

[4] “Indian Team Evens Series” The Honolulu Advertiser, May 31, 1941: p.15.

[5] “Oklahoma defeated Arizona,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 2, 1941: p.13.

[6] Al Murway, “J. Richard Ward _ _Springfield’s No. 1 Hero,” The Springfield Daily News (Springfield, OH), April 19, 1942: p.8.

[7] Al Murway.

[8] Al Murway.

[9] Al Murway.

[10] “McCrone Will Be ‘Stuffed’ With Baseballs,” The Charlotte News (Charlotte, NC), May 19, 1940: p.24.

[11] As of November 2023, we were unable to access to Shelby, North Carolina newspapers in our search for game summaries, box scores or news articles mentioning Ward with the Shelby Colonels ballclub. “Richard Ward,” The Sporting News Baseball Players Contract Cards Collection (accessed November 13, 2023).

[12] Al Murway, “J. Richard Ward _ _Springfield’s No. 1 Hero,” The Springfield Daily News (Springfield, OH), April 19, 1942: p.8.

[13] U.S. Navy Muster Sheet, USS Oklahoma (BB-37), Ancestry.com, January 31, 1941 (accessed November 8, 2023).

[14] Al Murway, “J. Richard Ward _ _Springfield’s No. 1 Hero,” The Springfield Daily News (Springfield, OH), April 19, 1942: p.8.

[15] U.S. Navy Muster Sheet, USS Oklahoma (BB-37), Ancestry.com, January 31, 1941 (accessed November 8, 2023)

[16] “80-G-411117 Pearl Harbor, (https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/wars-and-events/world-war-ii/pearl-harbor-raid/pearl-harbor-in-1940-1941/80-G-411117.html)” Naval History and Heritage Command (accessed November 14, 2023).

[17] Al Murway, “J. Richard Ward _ _Springfield’s No. 1 Hero,” The Springfield Daily News (Springfield, OH), April 19, 1942: p.8.

[18] Al Murway.

[19] William Thomas Ingram was a multi-sport athlete at the Naval Academy, lettering in football, basketball, and baseball. He graduated and was commissioned in 1938. “Lucky Bag, 1938.” Ingram was the son of Medal of Honor recipient Admiral Jonas Ingram and nephew of “Navy Bill” William Ingram, longtime Naval Academy football coach. Brothers Jonas and “Navy Bill” are inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. William T. Ingram retired from the Navy before serving as a business executive, notably for the Bunn-O-Matic Corporation.

[20] Al Murway.

[21] Ingram was a notable member of the 1938 Naval Academy team that saw many of its players make significant contributions during WWII and throughout their careers. See: “More Than Just a Game, (https://chevronsanddiamonds.wordpress.com/2021/04/17/more-than-just-a-game/),” by M. Shawn Hennessy, Chevrons and Diamonds, April 17, 2021 (accessed November 16, 2023).

[22] Admiral Trenchard Section Navy League, medals presented annually by Admiral Trenchard Section No. 73, Navy League of the United States, to the set of battleship turret pointers making the highest merit at short range practice to second set of pointers of USS Oklahoma Turret No. 3. – Named for Admiral Stephen Decatur Trenchard (1818-1883) – “48 Ships Are Given Awards,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 1, 1941: p.14.

[23] “Moments of Infamy – USS Oklahoma and USS Arizona Collide (https://www.facebook.com/PearlHarborNPS/videos/1833760050074554/?mibextid=zDhOQc),” National Parks Service (accessed November 14, 2023).

[24] It is a misconception that the USS Arizona baseball team was preparing to play the USS Enterprise’s aggregation on December 7, 1941, for the Pacific Fleet championship. That championship was captured on November 27, 1941, by the USS Oklahoma. However, baseball play was set to continue for the purposes of capturing the Navy’s overall athletics trophy which included securing points from football, basketball, tennis, swimming, rowing, and boxing. “Pearl Harbor, Nov. 29. – Battleship baseball teams of the United States Pacific Fleet will meet on navy yard recreation area diamonds on December 8-10 to thrash out the battlewagon unit championship. Winner of the elimination, which is played after the fleet championships won earlier this week by the USS Oklahoma, will earn 75 points toward the traditional Iron Man trophy for excellence in athletics.” – “Battleship Title at Stake,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 29, 1941: p.17.

[25] M. Shawn Hennessy, “Victory Dive! Navy Baseball in Paradise Through Championships and Tragedy, (https://chevronsanddiamonds.wordpress.com/2023/11/14/victory-dive-navy-baseball-in-paradise-through-championships-and-tragedy/_” Chevrons and Diamonds, November 14, 2023 (accessed November 16, 2023).

[26] November 27, 1941, was the fourth and last Thursday of the month but the Thanksgiving National holiday was not established for that day until the House Joint Resolution 41 was passed on December 9, 1941. See “Congress Establishes Thanksgiving, (https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/thanksgiving)” National Archives (accessed November 17, 2023).

[27] “Subron Four Nine Wins Pacific Fleet Ball Title,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 28, 1941: p.15.

[28] “Subron Four Captures U.S. Fleet Championship,” The Honolulu Advertiser, November 28, 1941: p.12.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] “Subron Four Nine Wins Pacific Fleet Ball Title,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 28, 1941: p.15.

[32] Chief Warrant Officer Henry A. Long, Jr., U.S. Navy (Retired), “Tactical Exercises Ended, (https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/1991/december/tactical-exercises-ended)” Naval History Magazine, December 1991, Vol.5, No.4, U.S. Naval Institute (accessed November 17, 2023).

[33] “The story of D. Weissman, Seaman, First Class, USS Oklahoma – Reports by Survivors of Pearl Harbor Attack, (https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/p/pearl-harbor-survivor-reports/uss-oklahoma-reports-survivor-pearl-harbor.html)”

Naval History and Heritage Command (accessed November 17, 2023).

[34] “Word is Awaited From Men in War Zone,” The Springfield Daily News, December 11, 1941” p.6.

[35] “Local Boy Wins Medal of Honor,” Battle Creek Enquirer (Battle Creek, MI), March 15, 1942: p.1.

[36] Two more medals were presented, in subsequent years, to veterans for their gallant conduct during the Pearl Harbor attacks.

[37] “FRANCIS CHARLES FLAHERTY (https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/francis-c-flaherty),” Congressional Medal of Honor Society (accessed November 17, 2023).

[38] Young S. B. (1998). Trapped at pearl harbor: escape from battleship oklahoma. Naval Institute Press (retrieved November 18, 2023, from https://search.worldcat.org/title/860901351?oclcNum=860901351).

[39] “Seaman Who Died on Ship Awarded Medal of Honor,” The Springfield Daily News, March 14, 1942: p.1.

[40] “JAMES RICHARD WARD (https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/james-r-ward),” Congressional Medal of Honor Society (accessed November 17, 2023).

[41] “Parents To See DSC Winner Honored,” The Honolulu Advertiser, April 5, 1953: p.20.

[42] “Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency Becomes Operational (https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/605362/),” U.S. Department of Defense, January 30, 2015 (accessed November 17, 2023).

[43] “Recently Accounted For (https://dpaa-mil.sites.crmforce.mil/dpaaRecentlyAccountedFor),” Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (accessed November 17, 2023).

[44] “SEA1 JAMES RICHARD WARD (https://dpaa-mil.sites.crmforce.mil/dpaaProfile?id=a0Jt0000000XgAYEA0),” Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (accessed November 17, 2023).

[45] “Jack Lummus, (https://www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/biographies/lummus_jack.html)”

[46] “Joe Pinder, (https://www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/biographies/pinder_joe.html)” Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice (accessed November 19, 2023).

[47] Dick Thompson, “Baseball’s Greatest Hero: Joe Pinder,” 2001 Baseball Research Journal, Society of American Baseball Research, December 1, 2001.

[48] “Ballplayers Decorated in Military Service, Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice (accessed November 19, 2023).(https://www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/decorated_in_combat.html)” Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice (accessed November 19, 2023).

[49] Thomas Gnau, “Springfield Medal of Honor winner will be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, (https://www.daytondailynews.com/community/springfield-medal-of-honor-winner-will-be-buried-in-arlington-national-cemetery/EVPH3VJELJFR7BQSKZDZ5COVZQ/)” Dayton Daily News, December 7, 2023 (accessed December 8, 2023).

Leave a reply to Harrington “Kit” Crissey Cancel reply