Regular readers of Chevrons and Diamonds might be accustomed to terminology that is employed when describing the photographs that are part of our collection – several of which have been published within our articles. It may seem straight-forward to casual collectors but the pursuit of old photos is not as easy as it may appear at the surface. I have been around photography for most of my life with countless hours behind the viewfinder, in the darkroom and in post-processing within the realm of digital imagery. I have experience with photo-duplication (I.e. taking a picture of a picture) in order to create a negative as well as the with the process of creating an inter-negative from a color transparency (color slide) – both practices have been relegated to the artistic end of the photographic practice rather than within the mainstream of photography.

Experience behind the shutter, navigating around in the darkroom and photographic editing does provide me with a measure of knowledge in recognizing certain aspects and details with photographs but extensive time spent with inherited vintage family photographs (ferrotypes, carte de viste, cabinet cards, real photo postcards, contact prints, etc.) throughout my life provided me with an introduction to this sphere of the hobby and led to further research on the older photographic practices and processes that are long-since retired.

Despite my knowledge and experience in this arena, I am far from being a subject matter expert however am fully capable of protecting myself from both over-paying or being taken by unscrupulous or neophytic sellers.

The precipitation for this article stems from the constant dialog among my colleagues surrounding the need to be able to knowledgably navigate the waters of vintage sports (specifically, baseball) photography collecting. With terms bandied about such as “Type-1, Type-2, Press, News, Wire service, Telephoto, etc.” understanding these terms poses as much of a challenge as it is in determining what a prospective vintage photo might be. Education in this area, while not fool-proof, can certainly provide collectors with enough tools to perform enough due diligence to make the right pre-purchase decisions.

The trend for articles published on Chevrons and Diamonds is anything but brevity and due to the significant amount of material that will be covered, the decision has been made to approach the various aspects of this subject through a series of articles.

At the risk of the following being misinterpreted as an outline (the list is merely a guide for what will be discussed in future articles), such focus areas will included covering the differences between professional and amateur photographs:

- Press/News

- Public Relations/Public Affairs images

- Wire service/Telephoto images

- Half-toned images

- Snapshots

- Contact prints

- Enlargements

When discussing professional photographers, we will spend some time touching upon some of the well-known shutter-snappers such as:

- George Grantham Bain

- Geroge Burke

- George Brace

- Tai Sing Loo

What should collectors look for in analyzing a print? We will discuss some of the basics that contribute to the value of vintage photographs such as:

- Scarcity

- Condition

- Originality

- Age

- Subject of the image.

Terminology is one of the more difficult topics in this arena due to the subjectivity and the randomness with which they are applied by collectors, sellers, graders and auction houses. Without attempting to re-author the terms, we hope to provide some semblance of standardization and meaning to otherwise (seemingly) useless nomenclature.

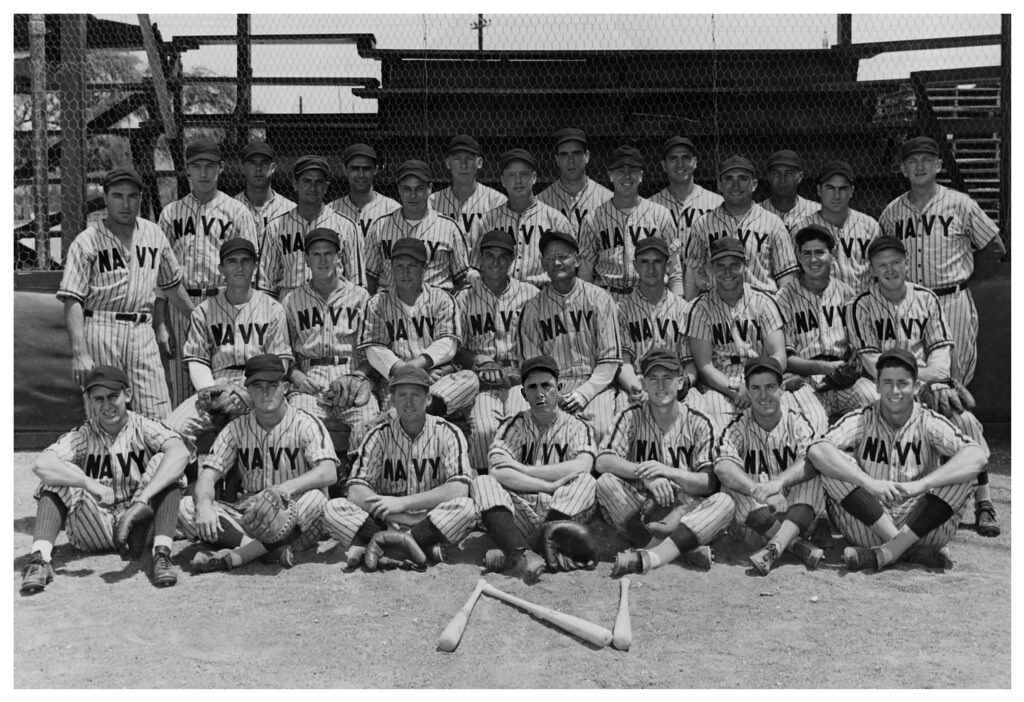

As the saying was first written, “one picture is worth a thousand words” which for a collector, only means that they are worth even more. The measure of detail that is captured on film (the uniforms, hats, spikes, gloves, location and venue that are depicted within each image is nothing short of treasured.

How does one determine the difference between a professional photograph and of one captured by an amateur?

- Composition

Learn how to recognize the manner in which professionals capture subjects and how they typically differ from that of a person taking a snapshot. Note where the subject is framed within the boundaries of the visible area; the back and foreground and where your eyes are drawn. A pro photog knows how to compose the image to emphasize what is being captured. Amateurs tend to place subjects dead center and miss the mark on infusing life into the subjects. - Capture

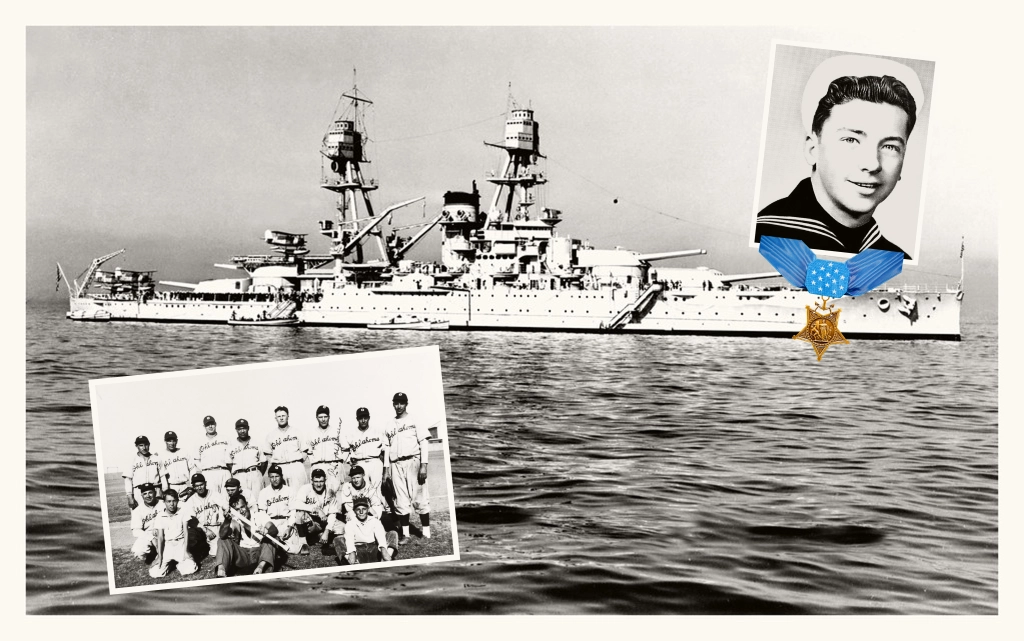

This image characteristic dovetails with the composition however this addresses the perspective of the image. In terms of baseball photography, professional photogs have access to areas that present a common vantage point in their image captures. It is normal to see close-up photographs of players on the field, in the dugout or even the clubhouse. Spectators shoot from a distance and elevation (such as from the grandstand) that has an entirely different subject-orientation from that of the professional. With regards to military baseball, amateur photographers could and often do have the same level of access that is typical for a professional.

- Exposure

Pay attention to the lighting of an image and how the photographer uses the light to enhance the subject. Is the subject faint or washed out (over or underexposed)? Are all of the important details distinguishable? Understanding the camera differences, especially within the realm of sports photography, professionals were employing large bodied cameras (such as a Speed Graphic made by Graflex) with “fast” lens that afforded the photographer with the ability to adjust aperture and shutter speeds. Also, the resultant negative (from the exposed and developed film) was substantially larger (4” x 5” or even 5” x 7”) than what was used by the average person. - Dimensions

A substantial portion of the Chevrons and Diamonds archive consists of personally or individually captured images that would be (and in many instances were) mounted on photo album pages. These photographs were typically printed using a contact-print method (the negative was laid directly in contact with the photo paper as it was exposed) producing an image that is the same size as the negative. These prints are most-commonly 2-¼” square, 2-½ x 3-½ or 3-½ x 4-¼ inches. Professional prints are enlargements made from the negative in dimensions of 5 x 7, 7 x 9 or 8 x 10-inches.

Certainly, there are more characteristics that one can employ to distinguish between these images with the most significant one being common sense. Stay tuned for the next segment in this series.

Leave a comment