Ansel Adams once said, “A photograph is usually looked at – seldom looked into.” With the proliferation of photographs and the ability to capture unlimited still and motion images at our fingertips, perhaps we have become desensitized to the value of what is contained within an image. What about the photographer? An image can be detached from its creator and shared and viewed millions of times in mere seconds without anyone taking a moment to consider who captured it. Can the same be said of vintage photographs?

Less than 20 years ago, when analog photography was at its zenith, photographers needed to be much more judicious and purposeful before depressing the shutter release due to the limitations of film on hand and the post-capture processing costs. For the more serious photographer, consideration was given to framing the subject, focusing and properly adjusting exposure settings before snapping the photo. Stepping back to the early decades of the 20th century, photographers had much more to contemplate in setting up their shot prior to capturing the image than their counterparts in the early years of the present millennium.

Noted baseball photographers from this era, including Charles Conlon, George Burke, Francis Burke, and Louis Van Oeyen, were laying the groundwork for the century and their work marks the pinnacle of vintage baseball photography collecting. These historic baseball images from the period known as the “Deadball Era” (1900-1920) garner considerable collector interest. Conlon’s and George Burke’s photo collections have been the subjects of multiple books which serve to draw more collectors into the vintage photography genre.

One photographer who captured countless baseball images beginning in the same era had a prolific career that spanned more than four decades. He captured some of the game’s greats and yet has gone wholly unnoticed by vintage baseball photo collectors. Chevrons and Diamonds did not take notice of this photographer’s work despite having a few of his images in our collection. It was not until we acquired a vintage photograph that we began to delve into his work and career.

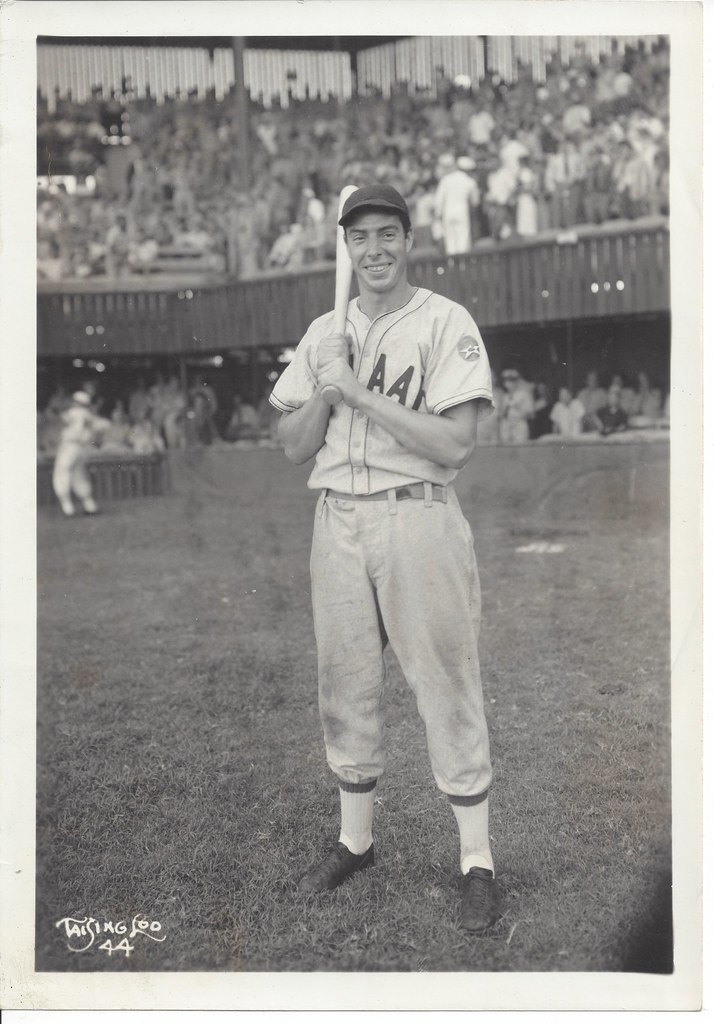

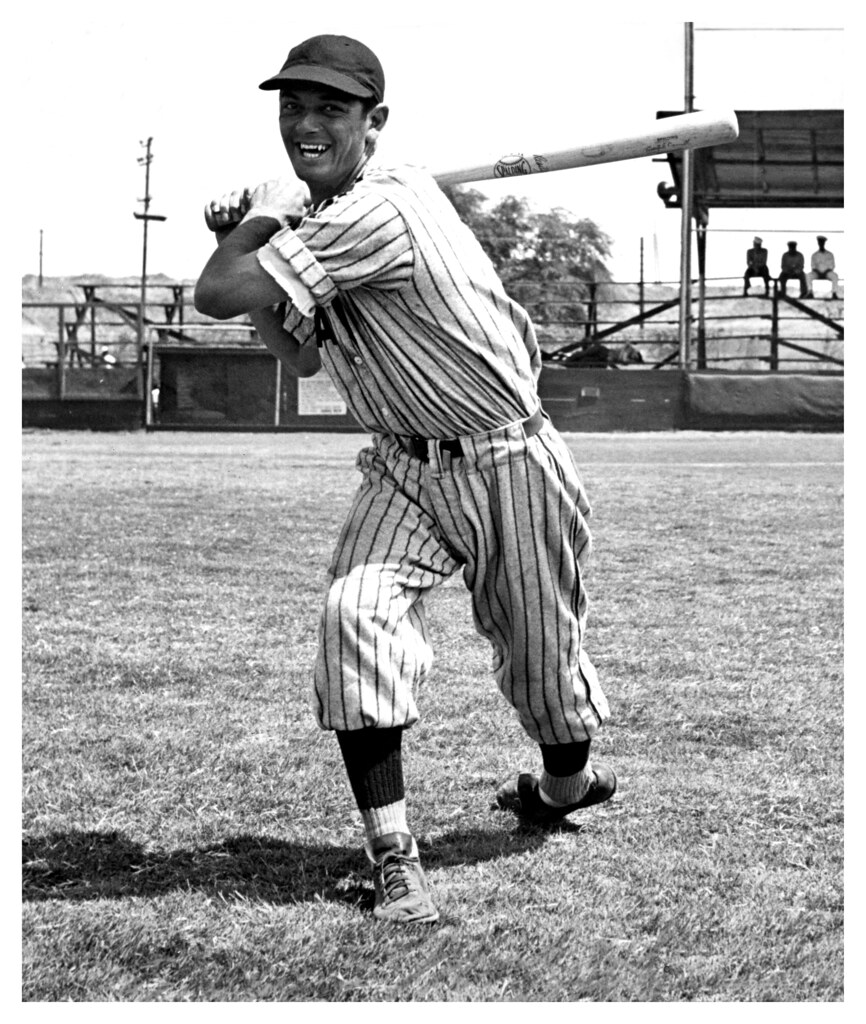

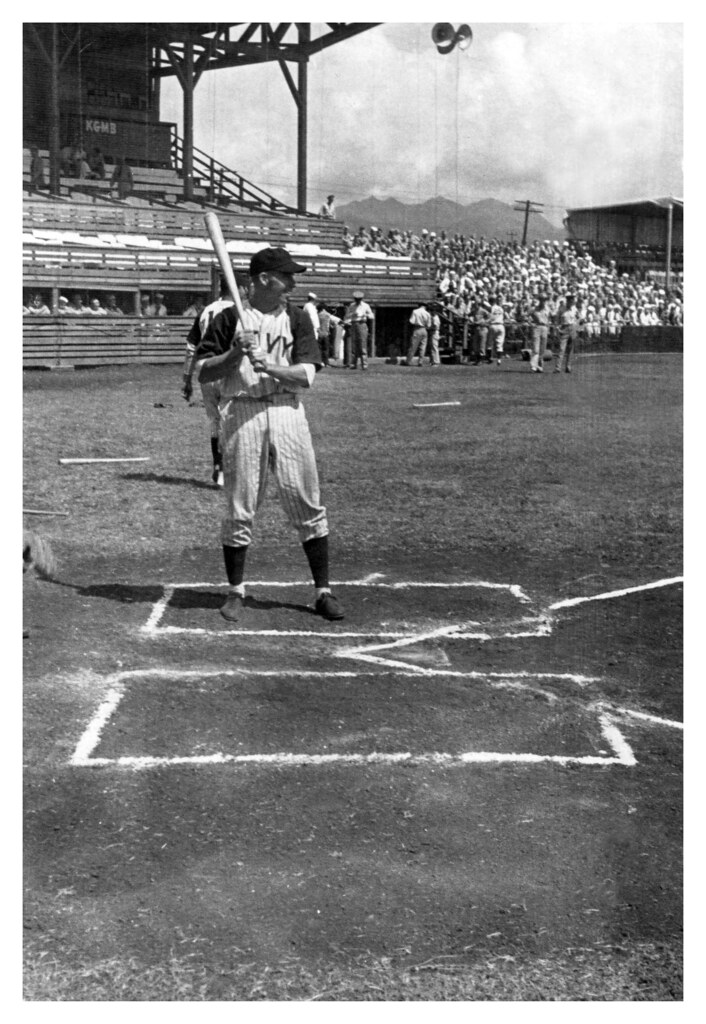

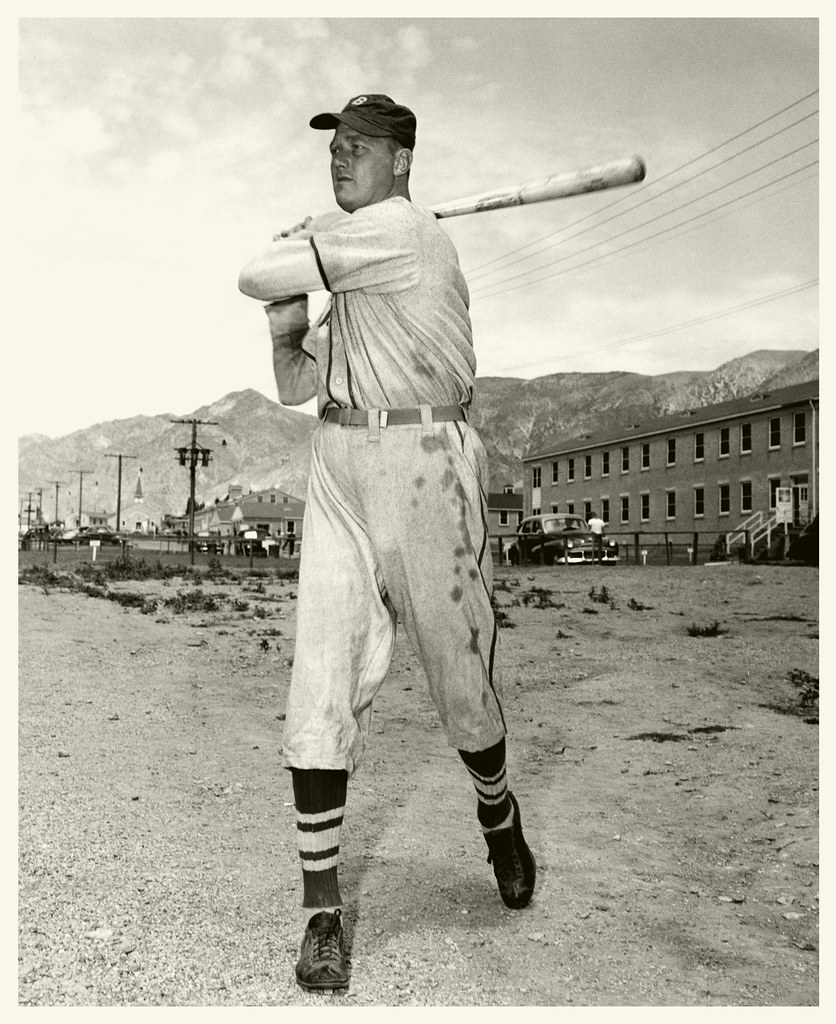

The photo that captured our attention showed Joe DiMaggio, posed with a bat on his shoulder in a wooden ballpark not too far from the backstop, with a bright smile on his face. His soiled gray wool flannel baseball uniform lacked the familiar New York Yankees pinstripes and featured the insignia of the Seventh Army Air Force affixed to the left sleeve with “AA” visible behind his left forearm. The vintage photo bore the markings in the lower left corner, “Tai Sing Loo, 44,” appearing to indicate the name of the photographer and the year that the image was produced.

Without any hesitation, we acquired the image ahead of conducting due diligence in researching it. Our familiarity with the Yankee Clipper’s wartime service and presence in Hawaii from June to September of 1944 was enough to pull the trigger on the acquisition. With several vintage photographs in our collection, the photographer’s name was still wholly unknown to us and catapulted our investigation into Tai Sing Loo’s photographic career.

While Oahu was the epicenter of the WWII service game from 1943-1945, baseball’s history in the Hawaiian Islands extended nearly a century into the past with the 1849 arrival of Alexander Joy Cartwright, who helped to establish the Knickerbocker Rules of Baseball on September 23, 1845. As within North America, the game’s popularity grew as it was increasingly adopted by the white settlers and native Hawaiians. Cartwright is said to have plotted a baseball field at Makiki Park that today still houses a ballfield named for the pioneer. Cartwright, who passed away on July 12, 1892, is interred two-and-a-half miles away from this site at the O’ahu Cemetery.[1]

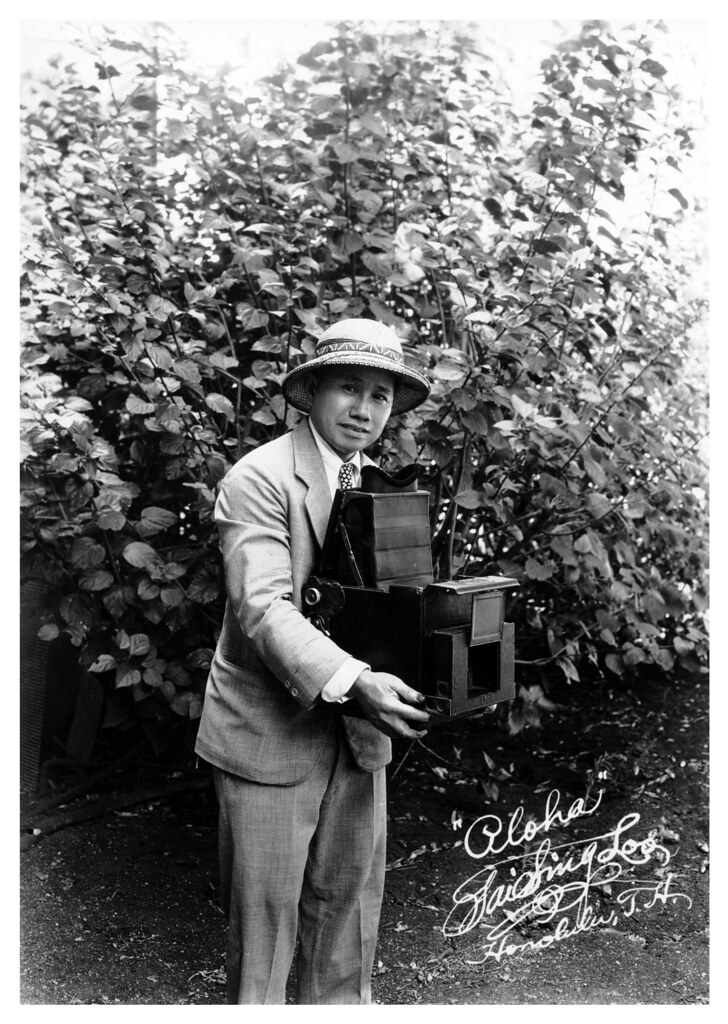

Six years before Cartwright’s death, Sam Choy Loo, a sign painter, and his wife Wong Shi Loo welcomed the arrival of their third son, Tai Sing Loo, on April 4, 1886, in Hawaii. The couple had immigrated to the islands from the Chinese mainland in 1879. By the time Tai Sing was 23 in 1909, he was working as a photographer for Alfred Richard Gurrey Jr.,[2] a photographer and son of the noted English landscape painter, Alfred R. Gurrey, Sr., at his art shop, located on Fort Street in Honolulu.

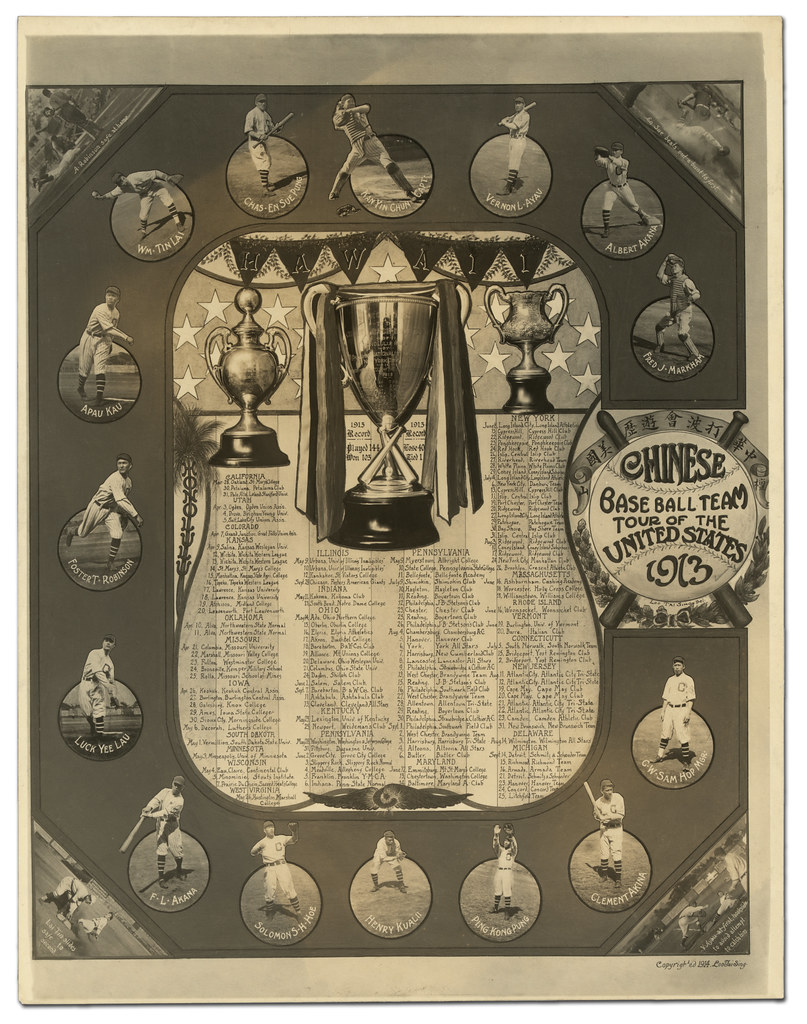

Loo’s earliest works remain largely unknown; however, in 1914 Loo photographed the Chinese University of Hawaii’s baseball team upon their triumphant return to the Islands after they had exerted their baseball dominance over collegiate, semi-professional and amateur baseball clubs across the United States. Upon their March 18, 1913, departure from Honolulu, west coast newspapers took note of the coming games to be played, “The team is considered the best in the Hawaiian Islands and has defeated all other Amateur nines of Hawaii. Although only college students, the members of the team have developed a keen likeness for the sport and have shown exceptional ability in playing it.”[3] Loo produced a broadside documenting the team’s success and incorporating 15 individual player photos, four action shots and images of the three trophies awarded to the club. Clearly, Loo was bitten by the baseball bug.

War was raging in Europe and the United States was immersed in the conflict, with troops committed to the fight and the Navy protecting convoys of men and supplies flowing from the Atlantic coast. In 1918, Tai Sing Loo was hired to work as the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard’s official photographer, and he went straight to work. The photographer packed his (then) vintage wooden glass-plate film camera and went up one of Pearl Harbor’s radio towers to capture a panorama of the facility. “I take panorama of my own free will,” Loo told the local newspaper. As Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels was soon to arrive to dedicate the new drydock (now known as Drydock Number 1), Loo set out to document the new addition to the facility, scaling a 760-foot-tall radio tower.[4] Tai Sing Loo “had captured Daniels’ attention by climbing a 760-foot radio tower to get an overhead shot of the base’s new drydock, a shot Daniels credited with selling a Senate appropriations committee on the need for a new repair base, piers and a submarine base,” as Frank Loo, Tai Sing Loo‘s son, told the San Pedro News-Pilot’s Verne Palmer in 1991.[5] As Frank Loo recalled, Daniels personally hired Tai Sing.[6]

In addition to publishing his official Navy-related images, the Honolulu Star-Tribune, one of Oahu’s largest newspapers, began to publish Loo’s sports photos. In December, Tai Sing Loo took a photo of the December 26, 1920, clash between the Hawaiian Islanders and a visiting Nevada team that was published on the front page of the newspaper’s sports section.[7]

The technology of cameras, film and processing was rapidly advancing in the early decades of the Twentieth Century. Sports photography was rising to the forefront of newspapers and periodicals and photographers demanded equipment that would allow them to capture both on field action and images surrounding the game. The Graflex Speed Graphic models became the gold standard for press and sports imaging. Like many professional photographers, Loo transitioned to the popular 5×7 Press Graflex model.8]

Loo was developing a reputation as a photographer who was up to nearly any challenge. After a few years of capturing change-of-command ceremonies, dedications, unit photos, and military sporting events, Loo was contracted by the Steam Navigation Company to capture places of interest on “the big island” of Hawaii.[9]

Tai Sing Loo continued with his naval photography work and explored the world around him behind the lens and shutter. He was one of the earliest photographers to capture the volcanic eruptions on the island of Hawaii, accompanying volcanologists Dr. Thomas A. Jaggar and Oliver Emerson to Kilauea in 1924. His photos, carried at home by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin,[10] circulated around the globe. On December 22, 1925, he was hired by the Red Star Line and embarked aboard the SS Belgenland, departing from Honolulu Harbor. He spent his time aboard ship working as the company’s official photographer for a three-month, 30,000-mile journey, capturing photos for the company around the world. After his cruise finished, Loo traveled from New York to San Francisco, also stopping in Los Angeles, before returning to Oahu. [11]

Loo was a hard-working photographer throughout the 1920s. His regular treks to photograph Kilauea’s eruptions, serving as staff photographer for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, creating photos for the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company’s tourism brochures, the Red Star Line’s World Cruise, and his job as the Navy’s official photographer, demonstrated Tai Sing Loo’s unrelenting work ethic and drive. His photographs of the volcanic eruptions were published in the National Parks information booklets and endured in subsequent publications for decades. Loo’s entrepreneurial spirit was unending as he advertised in the Honolulu Advertiser’s classified section, selling complete collections of island and volcano views.[12]

Disaster nearly befell the photographer when a fire broke out in his studio, located at 1155 Alakea Street in Honolulu. A local taxi operator observed smoke or flames just before 1:00 a.m. on April 21, 1930. The fire was extinguished by responding firefighting crews before any significant damage was sustained.[13] Had it gone unnoticed or spread, there is no telling how much of Loo’s work would have been lost.

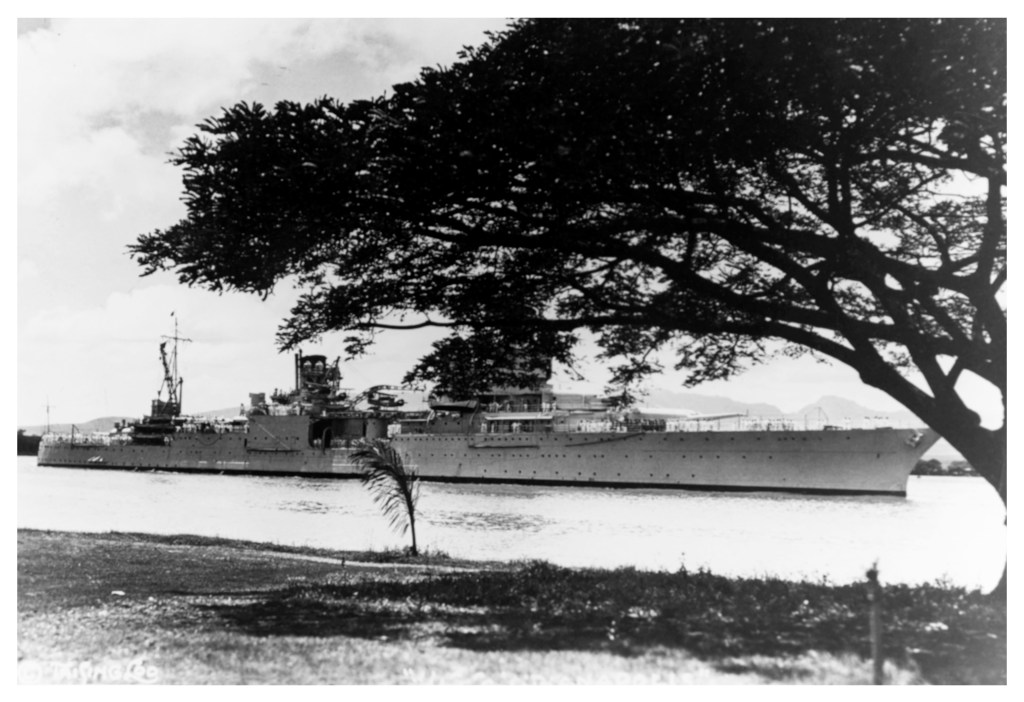

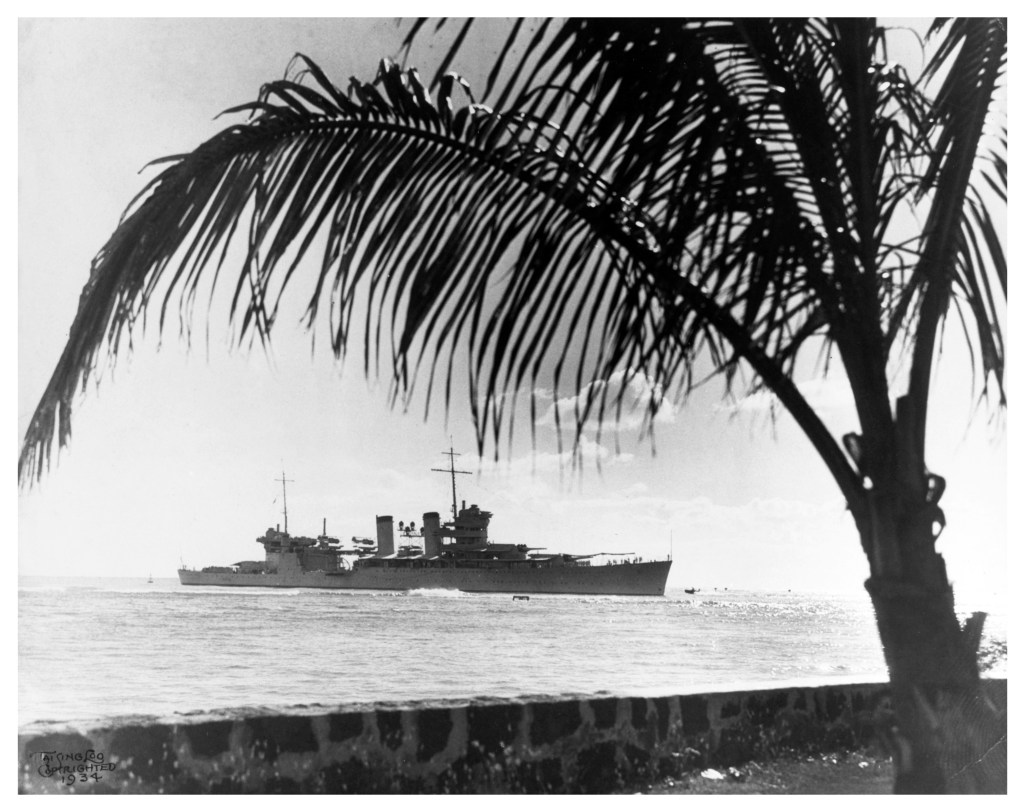

Throughout his tenure as the Navy’s photographer, Loo’s work was not limited to the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard. He captured construction projects throughout Oahu as the Navy constructed facilities at Kaneohe Bay, Barber’s Point, Aiea, and other sites. He photographed naval warships as they passed by Fort Kamehameha’s Batteries Barri and Chandler on their way into Pearl Harbor. His signature warship photos were captured with the vessel framed by the surrounding trees and sometimes showed the old fort’s seawall in the foreground.

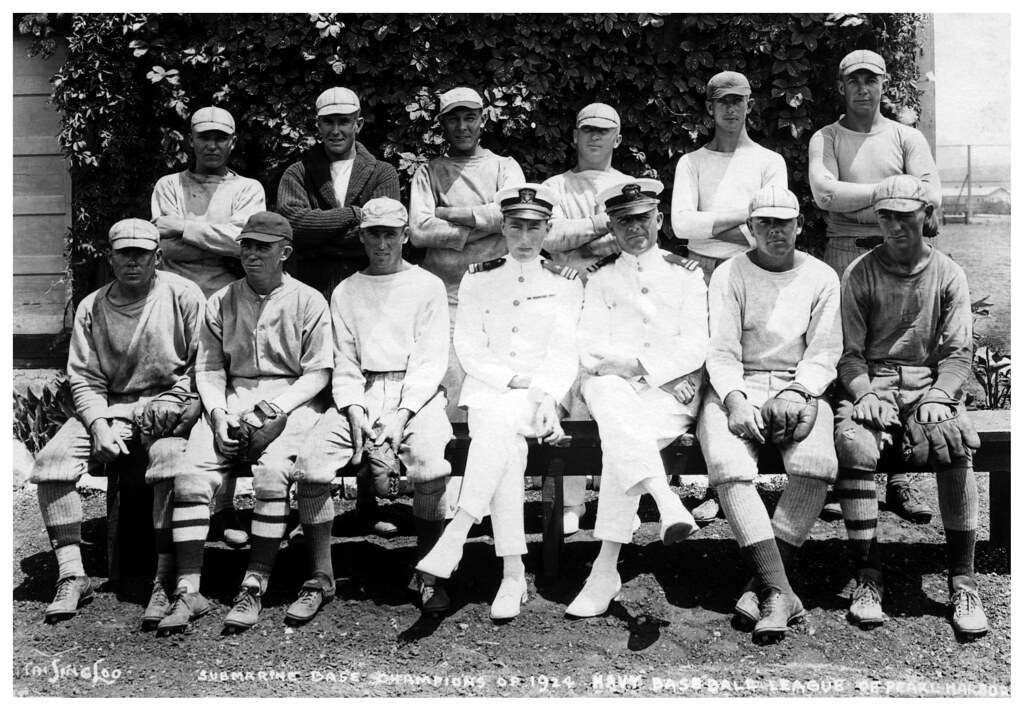

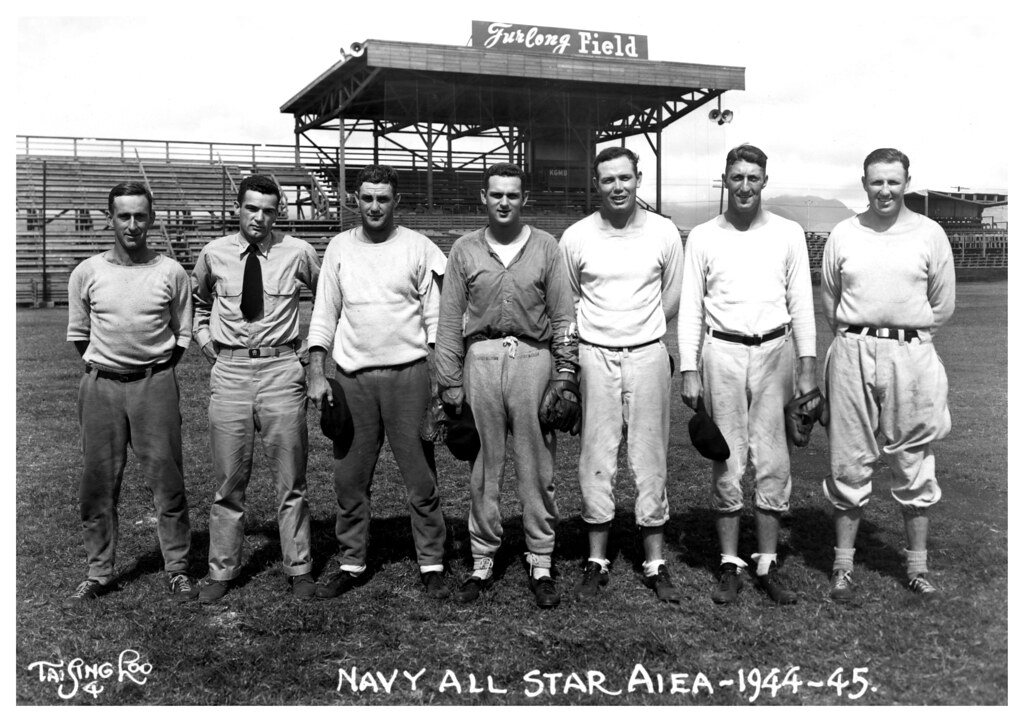

Loo had a knack for capturing an otherwise mundane subject and making it more interesting. Framing his subjects to include surrounding details without detracting from the central objective of the photograph, his images can be easy to spot by the trained eye. His sports images, predominated by team photos, are likewise easy to spot and not just because he was the Navy’s official photographer who had nearly unrestricted access, Loo was personable and liked by everyone who met him. Having Loo capture a basketball, football or baseball team photograph was as much a social activity as it was a documentation of the group or occasion. To the inexperienced beholder of his work, Loo’s photos may appear somewhat pedestrian however, he had a definitive style in how he saw moments through his lens and captured them on film. “To obtain a good photograph, one must have a fine subject, beautiful background, perfect light, an excellent camera – and a cameraman who knows all these things.”[14] The Honolulu Star-Bulletin was replete with Navy and Marine Corps championship team photos for all the Pearl Harbor Navy’s athletics.

Tai Sing Loo“To obtain a good photograph, one must have a fine subject, beautiful background, perfect light, an excellent camera – and a cameraman who knows all these things.”

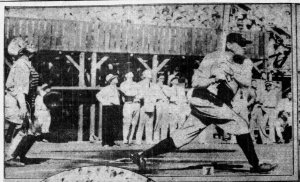

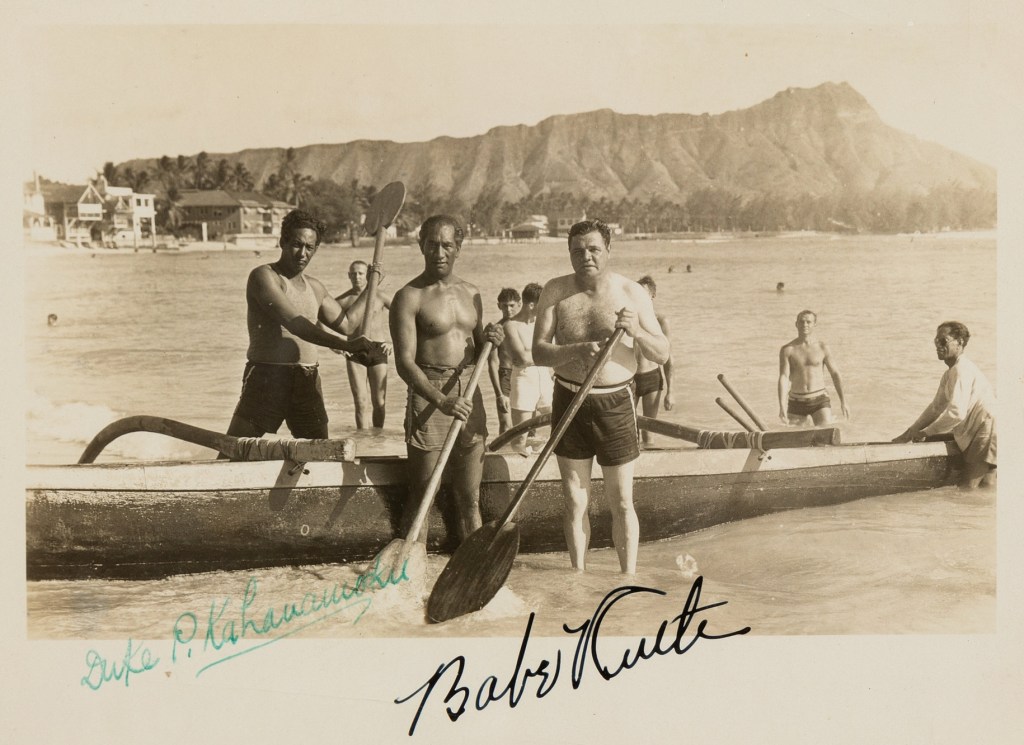

Despite Tai Sing Loo’s two decades of photographing sports including baseball, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin wrote of Loo’s newfound interest. “One of the latest addicts of the national pastime is Tai Sing Loo, the photographer. Loo says there’s nothing new about teams refusing to take a picture before a game. He has refused to walk under a ladder, too.”[15] The photographer’s work with the diamond sport had been ongoing since he covered the Chinese University of Hawaii’s 1913 mainland U.S. tour. However, in October 1933, the baseball bug bit down hard with the arrival of the game’s biggest star, George “Babe” Ruth. Loo captured several images of the Yankee slugger on Waikiki Beach with Duke Kahanamoku and at Honolulu Stadium as “The Babe” played in an October 22, 1933, exhibition game. During the game, Ruth played in the outfield and pitched as his All-Stars team defeated the 1933 Hawaii League champions, the Wanderers.[16] Loo captured the moment in the third inning when Ruth took an Earl Vida pitch deep to right field for a home run.[17]

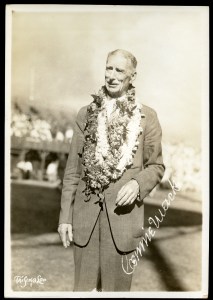

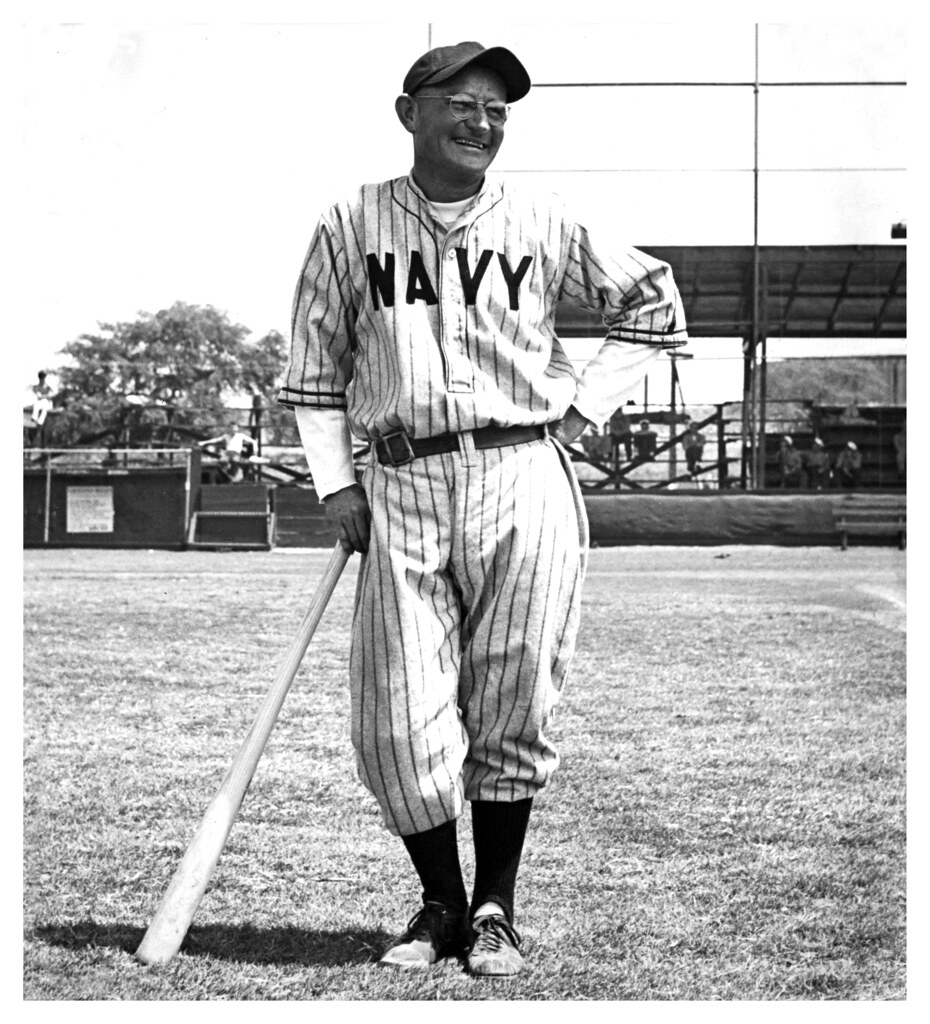

The following year, Tai Sing Loo experienced yet another encounter with major league baseball’s royalty as the American League All-Stars visited Honolulu during a stopover on their way to their 1934 tour of Japan. Led by Philadelphia Athletics owner and manager Connie Mack, the contingent of 15 players included Earl Averill, Lou Gehrig, Charlie Gehringer, Lefty Gomez, Frank “Lefty” O’Doul, Jimmie Foxx, Babe Ruth, and Moe Berg. During the visit, the American Leaguers faced an All-Star squad of Hawaiian players and defeated them handily, 8-1. Lou Gehrig hit the game’s only home run. [18] During the game, Loo was present to capture the action. “The big leaguers took their appearance casually. None of them was as busy as Tai Sing Loo, Navy Yard photographer. Tai, always in the thick of battle, parked too close to first base line and nearly lost an ear when Jimmie Foxx fouled a fast one down the base line.”[19]

Throughout the 1930s, Loo’s work continued with official Navy photos, Hawaiian scenery, wedding and bride images, newsworthy events and sports. In the decade, the Navy’s training exercises, dubbed “Fleet Problems,” were held in Hawaiian waters with the participating ships visiting Pearl Harbor before and after the events. Fleet Problems XIII (1932), XV (1934), XIX (1938) and XXI (1941) gave Loo plenty of opportunity to photograph a considerable number of ships and submarines entering the harbor. At the turn of the decade, the winds of war were blowing hard in Europe and across the Pacific.

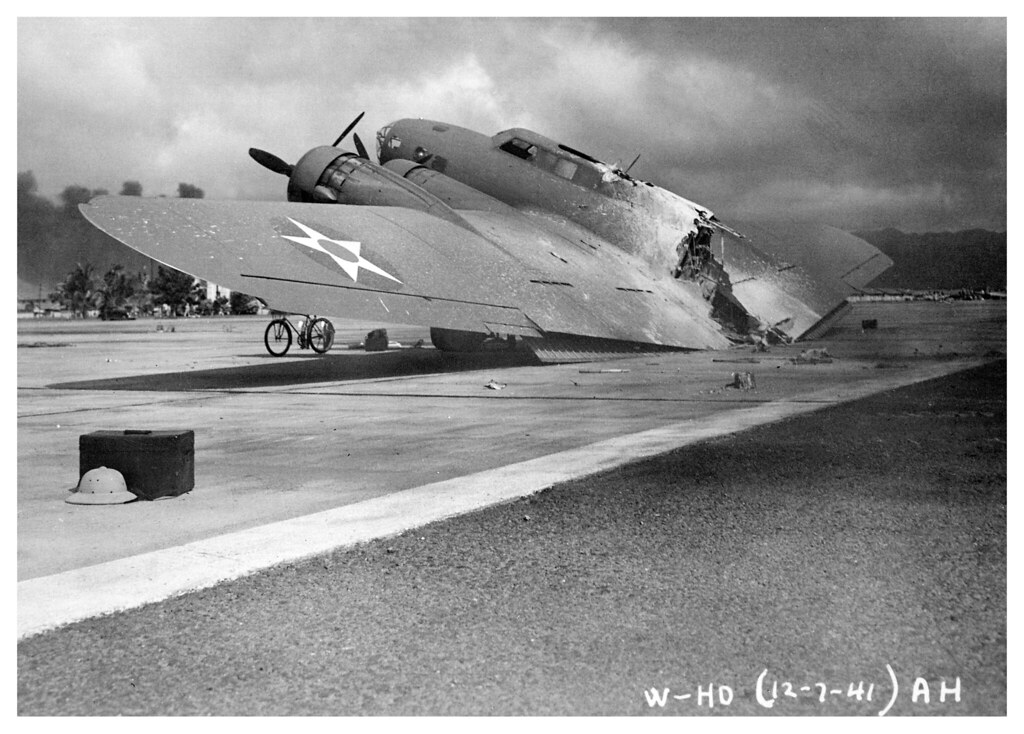

On Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, Loo was preparing to head to the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard to take photos of the Marine Detachment responsible for guarding the gates. Like so many people on Oahu and throughout Honolulu, he was surprised to see countless aircraft flying in low over the island and heading for Pearl Harbor as he waited for his bus to pick him up at the stop on the corner of Wilder Avenue and Metcalf Street, just two blocks from his home on Marques Street. “Saw the sky full of antiaircraft gun firing up in the air,” Loo wrote in his account two days later. “I call my friend to look up in sky, explain them how the Navy used their antiaircraft gun firing in practicing (sic), at that time I didn’t realize we were in actual war.”[20] Loo got off the bus at his normal stop for coffee when fire trucks raced by. He knew that he needed to get to the base as he was witnessing an attack in progress. He obtained a ride from a friend who worked at the shipyard to get to his studio, retrieve his camera and drive to Pearl Harbor posthaste. [21]

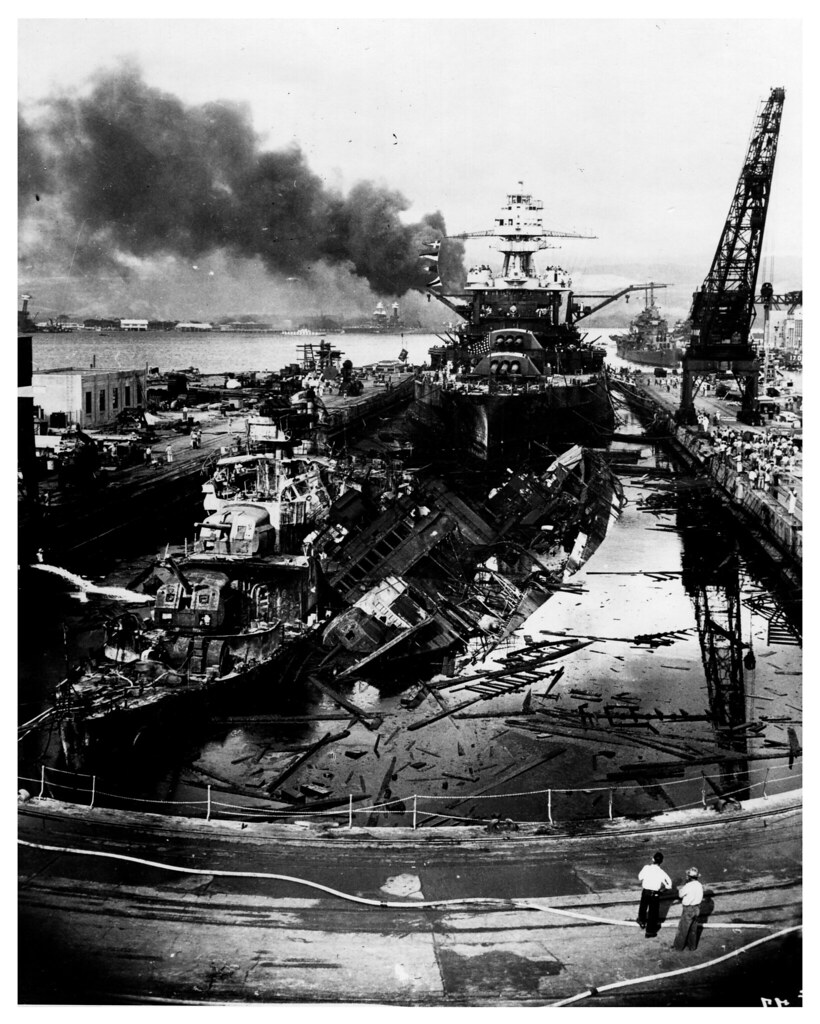

With the attack still underway and fires raging all around, Loo grabbed a steel hardhat and quickly painted it green with a single white stripe before heading over to Drydock Number One, where the battleship USS Pennsylvania and destroyers USS Cassin and USS Downs were on blocks. The fires surrounding the three ships were threatening to cook off the depth charges still stored on the aft decks of the two destroyers, and he began organizing men into fire-fighting teams to obtain hoses to beat back flames from the ordnance. Loo’s account describes in great detail his efforts throughout the day to keep depth charges from detonating and thus protect the crews and the drydock facility from certain doom. [22] Was it Loo’s personal connection to Drydock Number One that compelled him to risk his life to fight the fires or maybe his sense of duty and love of country?

After the fires were under control by late afternoon, Loo began working to ensure that crews were fed and hydrated. He worked through the day, making his way around the naval base. When he had the opportunity to do so, the photographer captured images of the damage. Perhaps his most notable Pearl Harbor attack photo showed the flooded Drydock Number One, full of flotsam and jetsam, with the USS Cassin leaning on the USS Downs and the Pennsylvania floating astern.

Loo’s firefighting effort and support of the troops and yard workers that day earned him recognition in March, 1942. “For outstanding loyalty, efficient action and disregard of personal safety, despite the danger from explosions as well as enemy strafing and bombing,” Tai Sing Loo was cited by the Navy along with numerous shipyard personnel for their unrelenting efforts to fight fires in the drydock area.[23]

According to the Defense Visual Information Distribution Service (DVIDS), Loo was also credited with assisting in breaking Japanese codes that were placed by local Japanese loyalists in bogus newspaper ads that detailed when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor would occur and what the aircraft formations were.[24]

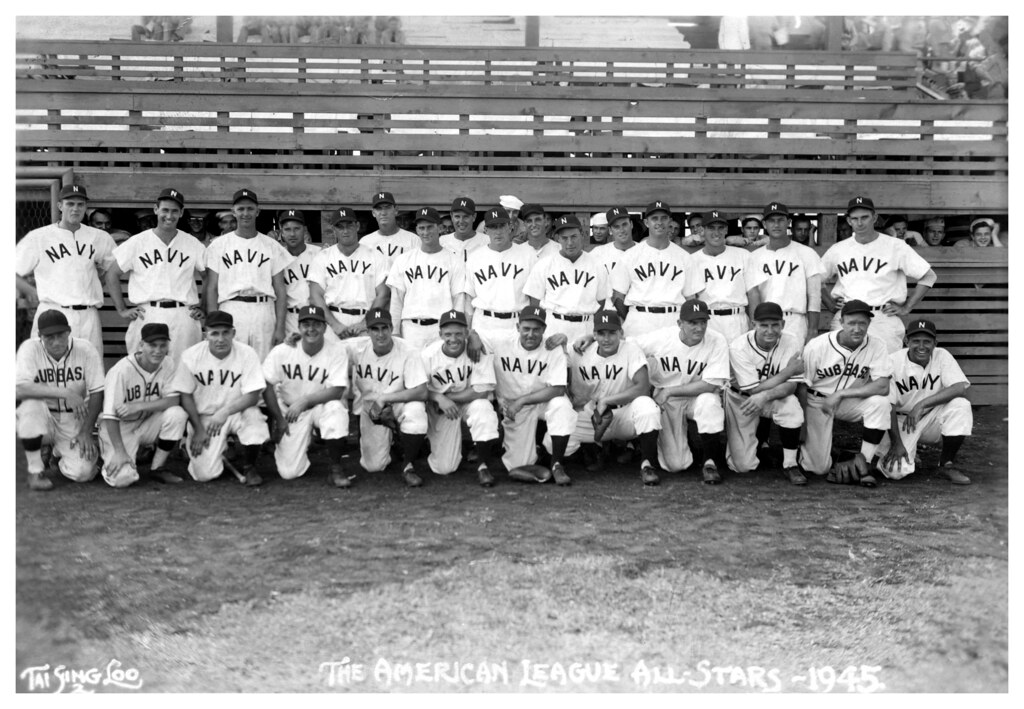

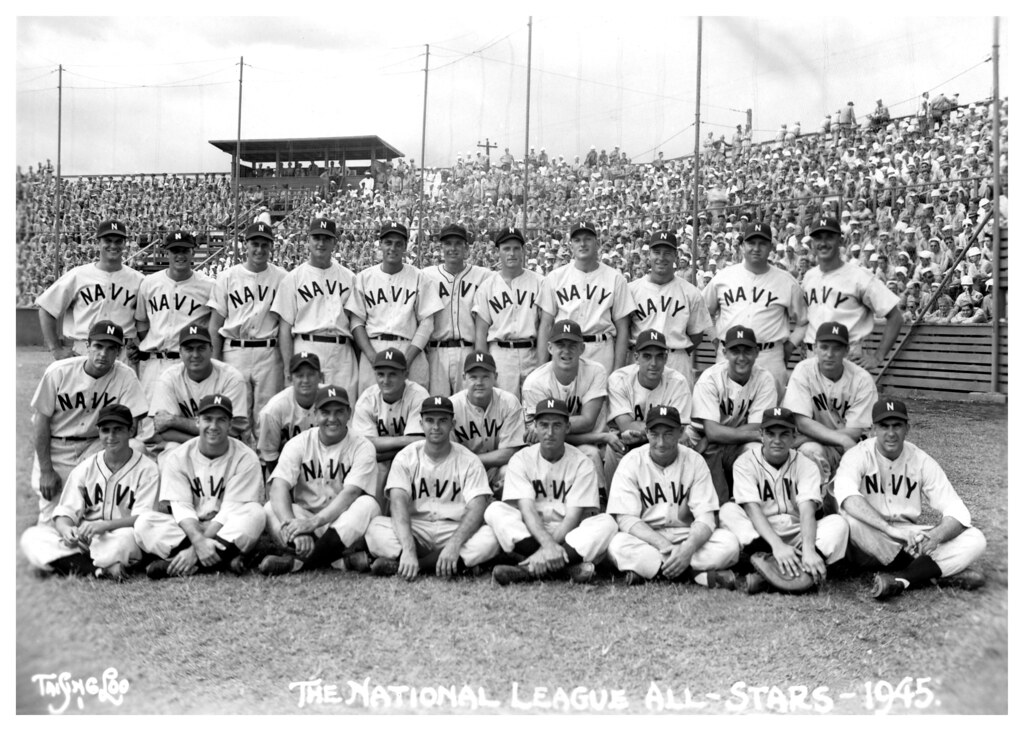

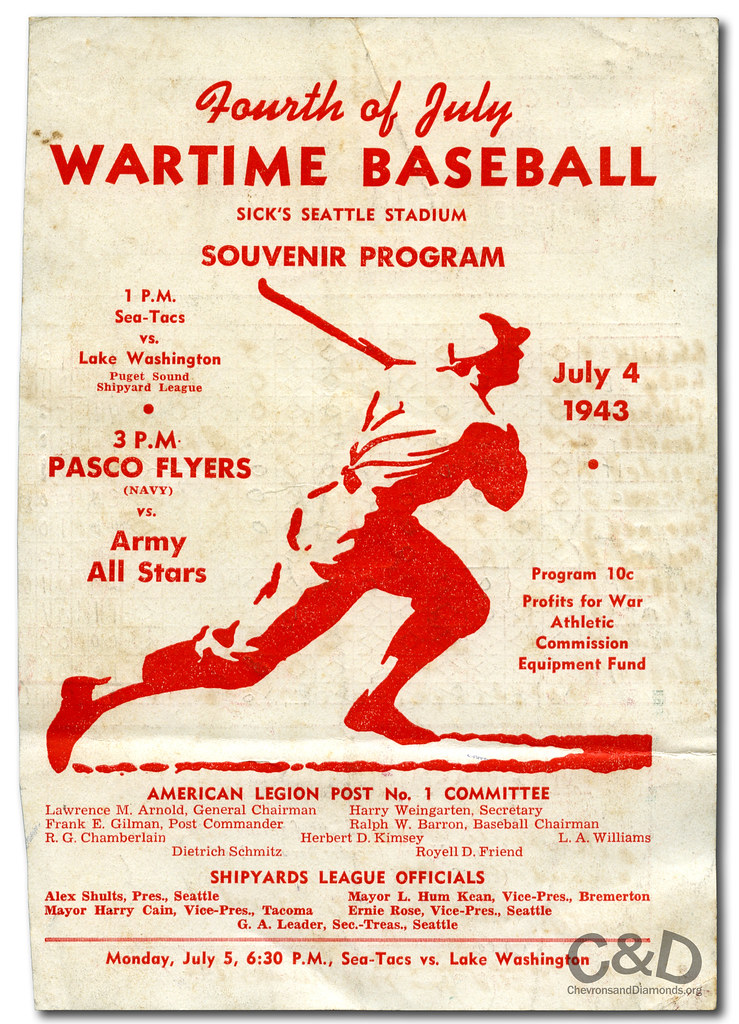

Major and minor leaguers began entering the armed forces to join the fight in the days following the Pearl Harbor attack. In the months that followed, former professional players trickled into the Islands and were assigned to area military commands. With baseball the preeminent sport in Hawaii, it made perfect sense to leverage the former professionals’ experience to field more competitive teams to boost the morale of the troops. For military participation in the Hawaii baseball leagues, the 1942 season was largely a wash but 1943 saw area command team rosters solidifying with professionals now wearing the uniforms of their nation.

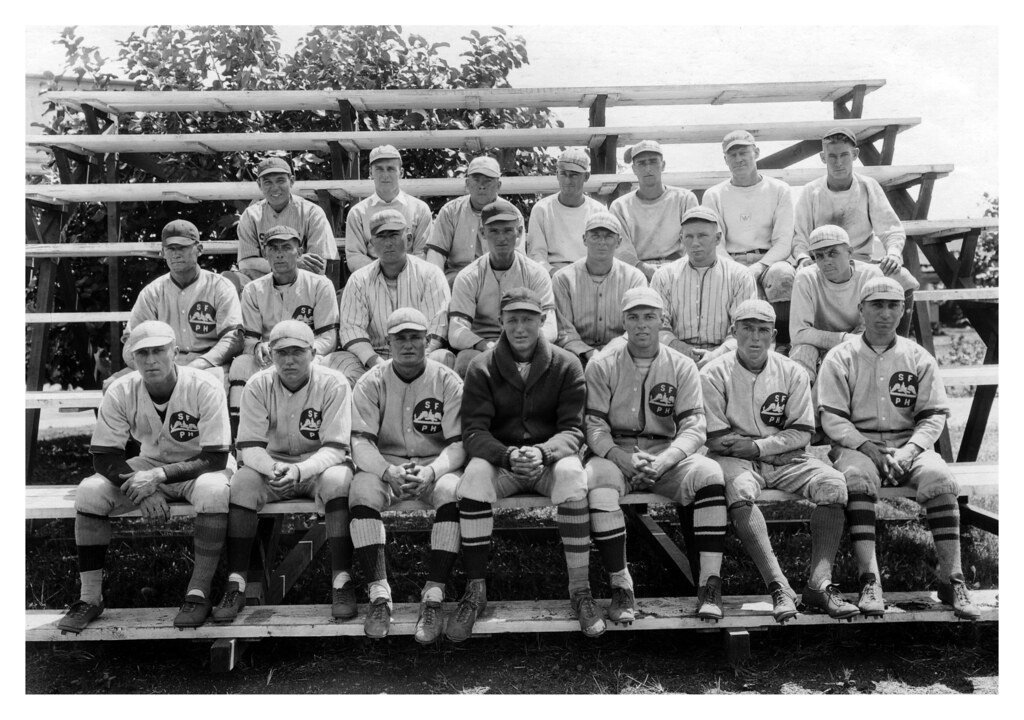

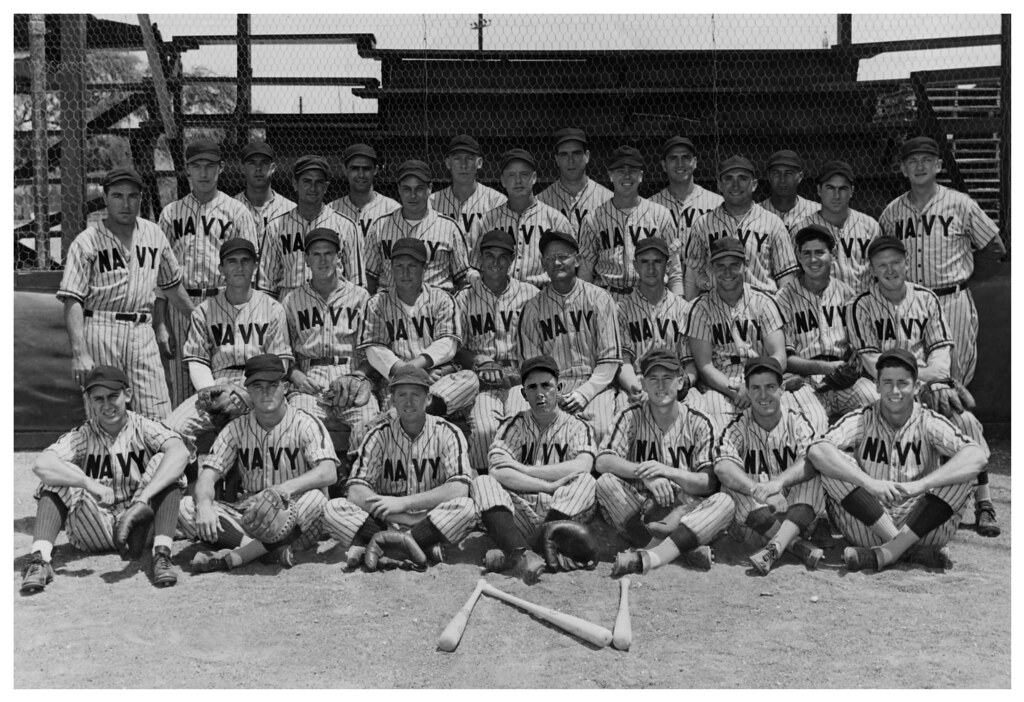

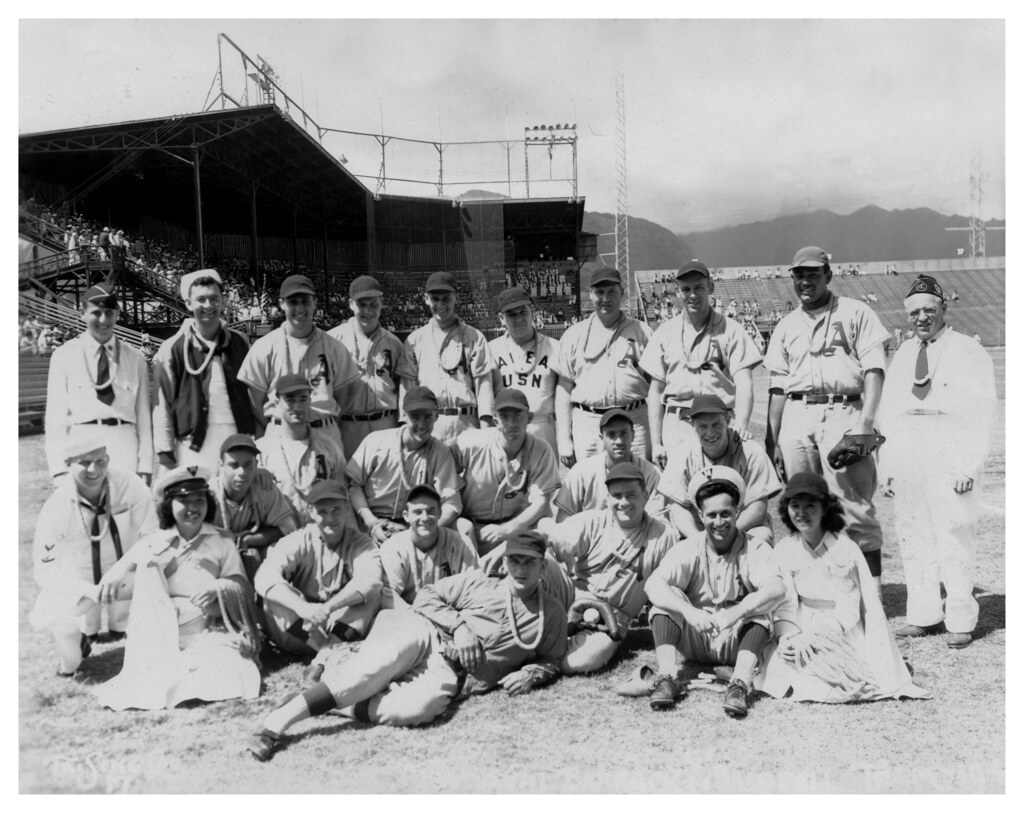

Second Row: (standing) Philip Simione (SS), Karl Gresowksi (2B) Clovis White (2B), Karl Fastnatch (OF), Maurice Mozzali (OF) Dutch Raffies (Coach), Oscar Sessions (P), Frank Hecklinger (1B), John Jeandron (3B) and James Brennen (P).

Third Row: R. A. Keim (P), William Stevenson (P), H. J. Nantais (C), John Rogers (OF), Richard Fention (P), Eugene Rengel (OF), John Powell (OF) and Jim Gleeson (OF).

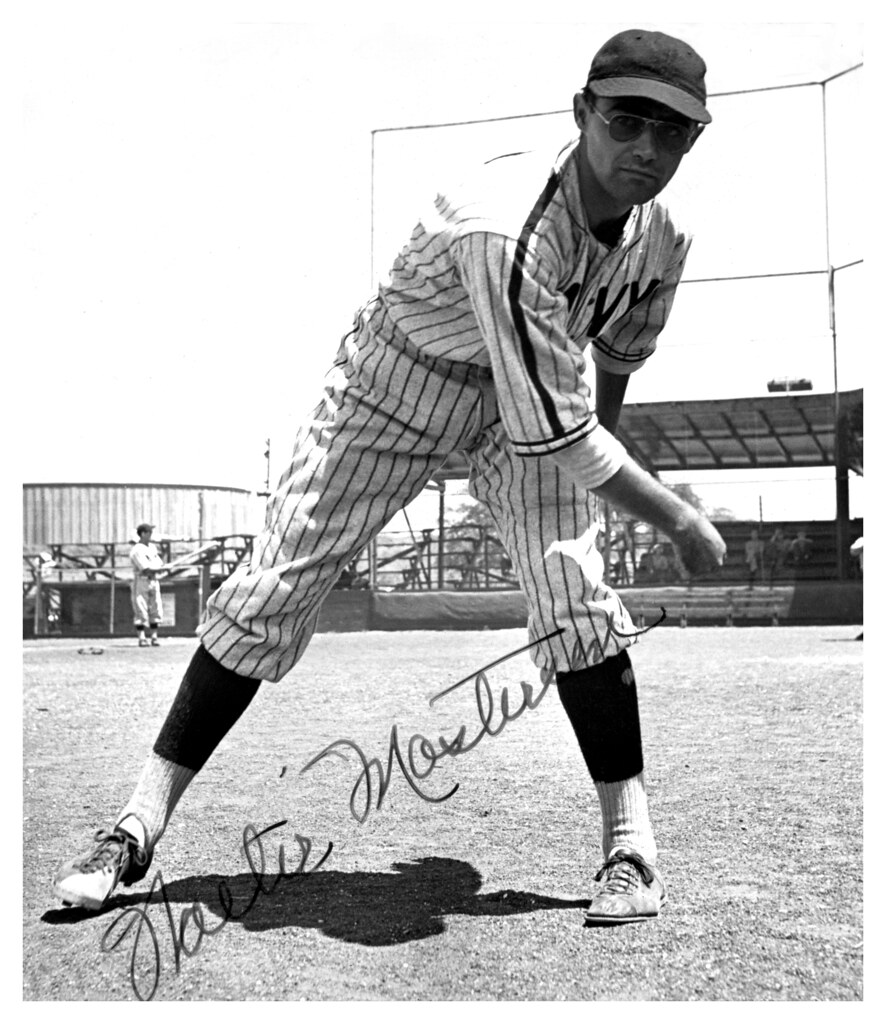

Fourth Row: Rankin Johnson, Walter Masterson, Arnold Anderson, Charles Medlar, Ray Volpi and George Henry – all pitchers (Tai Sing Loo/Chevrons and Diamonds Collection).

For Loo, the military baseball world was centered at Pearl Harbor, with the Submarine Base “Dolphins” roster featuring former Senators pitcher Walter Masterson, centerfielder Jimmy Gleeson of the Reds and Philadelphia Athletics hurler Rankin Johnson among the mix of former minor leaguers and semi-professional players. Loo captured the team in a series of photos taken at the Dolphins’ home park, Weaver Field, on the Submarine Base.

As the season was getting underway in 1944, more ballplayers had arrived and were assigned to Army, Marine Corps and Navy bases, stacking service teams with increasingly better talent. The Navy saw the arrival of future Hall of Famers Pee Wee Reese and Johnny Mize as well as a host of star talent including Hugh Casey, George Dickey, Jack Hallett, Barney McCosky, Tom Winsett, Bob Harris, and Al Brancato.

With the Sub Base team capturing the three significant league championships in 1943, Army brass took corrective action and shipped a host of stars to Hickam Field to stack the cards in their favor. The 7th Army Air Force team was transformed into a military version of the New York Yankees, complete with three former Bronx Bombers who were destined for Cooperstown. Charlie “Red” Ruffing, Joe Gordon, and Joe DiMaggio headlined a roster that included future major league all-stars and stars of the minor leagues. The 7th would dominate the 1944 season as Oahu became the epicenter of baseball while the actual major league rosters were absent their star players due to wartime service.

Loo and his camera were front and center for what was arguably the best baseball being played anywhere on the planet. As the Navy’s official photographer, he had access that no civilian camera jockey could dream of attaining. As military leaders pulled back from playing games at Honolulu Stadium in favor of military ballparks, Loo’s access kept him as the central figure in documenting the games with his camera.

For much of his career, Loo shot with his Press Graflex, which used five-inch by 7-inch glass plates to capture images. During his processing, he would typically mark the lower edges of the glass plate negative by etching the emulsion to indicate ownership of his images. His photographs were easily recognized with his trademark markings as they graced the pages of newsprint. Sometime in the 1930s, Loo switched to film. His images were regularly published in multiple Hawaii newspapers including the Honolulu Advertiser and Star-Bulletin, but his markings were gone from the news pages. It is unknown if Loo refrained from marking his photos or if the newspaper photography editors cropped the markings out.

Loo’s Image Marks

While he did produce some enlargements, most of Loo’s photos were 5×7-inch contact prints, printed directly from his glass negatives. From his earliest days, Tai Sing Loo employed at least six variations of markings, all of which featured his full name. Some photos were marked with the subject of the photo either centered across the bottom or on the bottom left corner beneath his name. Some images included a three-digit number. Those that he marked were done so without consistency. None of Loo’s photos were marked on the reverse side.

Below are a few examples of the photographer’s marking variations:

Tai Sing Loo served as the 14th Naval District’s photographer until he retired in 1949 after 31 years and six months of continuous service. Loo was beloved by Navy and civilian personnel alike. Director of the 14th Naval District’s civilian personnel, Commander Gordon P. Chung-Hoon, bid Loo farewell. Hoon, Hawaiian-born of Chinese ancestry, was a heroic former commanding officer of the destroyer USS Sigsbee (DD-502). His gallantry and bravery led to his being conferred the Navy Cross and Silver Star medals.

Loo’s Navy career led to his capturing photographs of U.S. presidents, countless admirals and generals, movie stars, legendary athletes, hundreds of ships, and aircraft, over 100,000 civilian workers’ identification badges, sports teams, unit photos, buildings and ceremonies. His work amounted to a photo archive that is nearly incomprehensible in its totality.

Loo’s retirement marked the end of his Navy career but not the end of his love of photography. He continued to take photos for the rest of his life. On August 26, 1971, not long after the Sheraton Hotel on Waikiki opened (next to the Royal Hawaiian), 85-year-old Loo was on the top floor to take photos of the view from the tall building. Eventually, Tai Sing Loo suffered a myocardial infarction that took his life. “He had a heart attack and died doing what he loved best,” his son Frank Loo told Verne Palmer of the San Pedro News-Pilot in 1991.[25]

In the years following Loo’s retirement and passing, his photographic archive, consisting of paper prints and several cases of glass and nitrate negatives at Pearl Harbor, was sent to the National Archives. By the 1980s, the National Archives staff decided to deaccession the collection and since the topical subject of the work surrounded Pearl Harbor, they reached out to the Hawaiian Historical Society as the most likely recipient. Lacking appropriate space to house the collection, the Society folks recommended the Arizona Memorial Museum Association. By the end of the decade, most of the collection was digitized, reduced, and archived, with the total images numbering less than 10,000.[26]

The photographs that are available on the market were largely in private collections for many years and were given to the original recipients by the photographer himself. When he shot a unit baseball team photo, he was known to produce multiple copies and distribute them among the folks in the photos. It was not out of the ordinary for Loo to provide ship photos to officers and crew who requested them. Though many of his images were housed in the photo morgues of the Honolulu Advertiser and Star-Bulletin, we have yet to see any surface in the collector marketplace.

In addition to original examples of Loo’s work, his photos were used as the basis for many printed tourist postcards. To the untrained eye, these press-printed postcards may appear to be the same as a real photo postcard but upon close examination, one can see the halftoning “dots” of the mass-produced printed cards.

While Tai Sing Loo was a prolific photographer, his sports images constitute a small percentage of the body of his work. However, due to the preponderance of them being armed forces-related, his baseball photos are highly sought after for the Chevrons and Diamonds Collection.

[1] Alexander Joy Cartwright Jr., Findagrave.com (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/1283/alexander-joy-cartwright), accessed August 18, 2023.

[2] Alfred Gurrey, Artist Biography and Facts (https://www.askart.com/artist/Alfred_Richard_Sr_Gurrey/123952/Alfred_Richard_Sr_Gurrey.aspx), askArt.com, accessed August 18, 2023.

[3] “Chinese ‘Cobbs’ On Way to U.S.,” Los Angeles Evening Express, March 20, 1913: p.19.

[4] Mark Walters, “Loo’s Initiative Gave Navy Aerial “Blueprint’ of Pearl Harbor Layout,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 7, 1961, p.18.

[5] Verne Palmer, “One Man’s View,” San Pedro News-Pilot, December 05, 1991: p.13.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Some Graflex Shots of Nevada-Hawaii Gridiron Clash,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 27, 1920: p.6.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Inter-Island Co. To Issue Booklet,” Hawaii Tribune-Herald (Hilo, Hawaii) ·October 16, 1924: p.5.

[10] “First Pictures of the Volcano Pit As It Appears Today,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Jun3 3, 1924: p.10.

[11] “On World Cruise: Tai Sing Loo Will Sail on Belgenland Bound Rownd Globe,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 21, 1925; p.9.

[12] “Classified Columns: Specialty Shoppers’ Guide,” The Honolulu Advertiser, June 17, 1928: p.30.

[13] “Fire Extinguished,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, April 22, 1930: p.18.

[14] “They Ought to Know,” The Honolulu Advertiser, November 3, 1927: p.12.

[15] Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 7, 1932: p. 26.

[16] M. Shawn Hennessy, “Dutch” Raffeis: The Navy’s Own Flying Dutchman,” (https://studiogaryc.com/2023/03/10/dutch-raffeis/)” The Infinite Baseball Card Set, accessed August 23, 2023.

[17] William Peet, “Babe Ruth Thrills 11,000 Fans, Hits Home Run: Bambino Pitches Last Two Innings,” The Honolulu Advertiser, October 23, 1933: p.10.

[18] William Peet, “Big Leaguers Beat Hawaiian Stars, 8 To 1,” The Honolulu Advertiser, October 26, 1934: p.12.

[19] Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 26, 1934: p.10.

[20] Tai Sing Loo, “How Happen I Were at Pearl Harbor—On the Morning of Sunday, 7th of Dec. 1941,” Proceedings (Vol. 88/12/718), December 1962.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] “Navy Gives Citations To 106 P.H. Workers,” The Honolulu Advertiser, March 23, 1942: p.2.

[24] Amanda Cartagena-Urena, “Who is Tai Sing Loo? (https://www.dvidshub.net/news/410745/who-tai-sing-loo)” DVIDS, accessed August 23, 2023.

[25] Verne Palmer, “One Man’s View,” San Pedro News-Pilot, December 5, 1991: p.14.

[26] Burl Burlingame, “Pictures of Pearl,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, May 2, 1989: p.21-22

Leave a comment